The Immigrant Quilt Project is a collection of unedited and uncensored undocumented immigrant narratives, stories and experiences as shared by participating community members. These narratives attempt to weave together the experiences of undocumented immigrants from various part of the world; providing a space for the API (Asian – Pacific Islander), Black (African and Afro-Caribbean), European, Latin American and other groups of immigrants who currently find themselves in the United States as undocumented immigrants. This self-narrative project not only retells the stories of undocumented immigrants specifically here in California through conversations, interviews, documents (letters or photographs), and any other forms of personal archival records, but also serves as a trail maker for the shared experiences of all immigrants across the continental United States. This project also attempts to contribute to the mobilization and representation of the undocumented immigrant communities in the United States, by stitching together the self-spoken narratives of undocumented immigrants, centered in intersectionality, acknowledgement, and respect of everyone’s existence. Through this process, each participating story becomes a physical piece of a quilt under production. We invite and encourage all undocumented peoples living in the United States to step out of the shadows and help us in reshaping the narrative of immigration in this country.

Memories We Left on the Border: Part 1

Upon the breaking of dawn in the early spring of 1994, the Chiapanecan skies melted onto our skin. The precipitation of the morning dew tapped silently on the leaves of the trees, like a distant memory returning to our minds. Water ran down the ragged edges of the palm fronds that formed the roof to our house, embedding the silhouette of the precipitations’ trickle on the ground. Rings formed like voiceless echoes, quietly vibrating into the distant and darkened edges of our motherland. The early morning was warm, clouds of dust lifted from the arid, hungry, and unpaved land. My family and I stood there, in the middle of our yard; our tears melted with the precipitation and trembled at our feet. Torn away from my grandmother’s arms that early morning, we were rushed into a triciclo (tricycle) and began our journey to the United States.

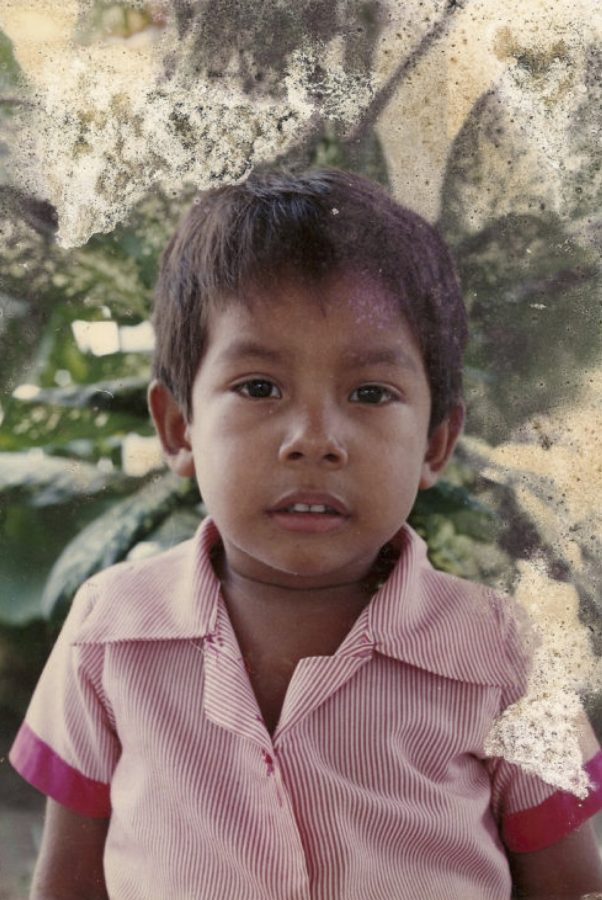

My life began in 1987, upon conception. My mother had lived a volatile pregnancy from 1987-1988, finding herself in a deep depression. My father had been significantly abusive to my mother during her pregnancy with me, bringing other women to the house, and in such occurrences, beer bottles thrown at her. After his abandonment and their separation, my mother entered a time of emotional and financial instability. By 1990, my mother was unable to care for us due to unemployment, a lack of resources, and the unstable guerilla war of Guatemala. Hunger and death decimated the Guatemalan people—bullets and machetes, swung and swarmed like abejas de un penal (swarming bees). It seemed that our feet had always been one step ahead of us, running from fear and attempting to catch another day of life before the sun went down. Jumping on black tire rafts across the tremulous waters of the Rio Suchiate, my mother, my sisters and myself crossed the Guatemalan and Chiapas, Mexico border, and dropped us off with my grandmother.

My grandmother raised us over the course of four years, in which she fed us, clothed us, but most importantly, loved us. She was a stern woman, but her love for me melted like paletas de hielo con sabor de tamarindo (frozen tamarind popsicles) in the sun. The sugary extract of her love made me inseparable from her side. She was my first love, and until today at the age of 28, I long to return to her embrace. I long to return to those young days when the softness and creases of her aging skin enveloped me with care and tenderness. As I sat on her lap and fell asleep in her arms, I dreamed wonders within her silent hum. But the days which seemed endless as a child, have now become endless memories of innocence. I sat on the dirt road across from my grandmother’s home, awaiting to see my mother return. I sat there under the burning sun, tossing rocks and waiting as triciclos (tricycles) turned into the road that led to our house. I was overcome with excitement as I heard the rustle of the bicycle tires and the ringing of the driver’s bell. But I woke up from a terrible nightmare with the *ring*ring* of the bell. I longed to be in the arms of my mother, embraced by the warmth of a woman I only remembered from photographs.

In 1993, my grandmother received notice from my mother that she would be returning for us. By this time my mother had begun a new life in California, and had saved enough money to bring us to the United States. She had also grown weary of our safety because of the rumors that civil war would break in Chiapas. And this was the case; On January 1, 1994 the Zapatistas revolted in Chiapas, Mexico, after being neglected and overlooked by the Mexican government in the distribution of resources provided by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). With Chiapas forgotten, we left everything behind. I remember I scurried about the yard in the dark, collecting my toys, as I asked my grandmother to give them to a friend of mine from school; a name I have since then forgotten. We hugged our relatives tightly, and I cried in the arms of my grandmother as we said farewell. That morning, we left behind a woman whose love could never be taken from my heart, even by a border and the miles of land that separates us. I could find my happiness in her eyes, and in her laughter I found the comfort of a child’s lullaby.

As we boarded a triciclo (tricycle) that morning, we traveled to Tuxtla Gutierrez, Chiapas, in which we boarded a plane to Tijuana, Mexico. Once in Tijuana, my mother had hired a 19-year-old coyote that would help us cross the border. Afraid in the Sonora Dessert, the arid night enveloped us in its anonymity. That night immigration patrol had been patrolling the area. All I knew was that we were to stay silent and hide. The helicopter roamed above us, and Border Patrol walked the area by foot. At the hand of my mother, we were pushed into a dark bush against a cliff, in which we were hidden to avoid getting caught. One of my sister’s recalls that while in the bushes, she saw a skunk and was about to scream. The coyote screamed at us and told us to be quiet. She put her hand over her mouth in order to avoid screaming, she was afraid. At that moment a border patrol official walked by our area, flashing the area with a flashlight. Because we had been laying on the floor, and avoided all movement, he went away. We ran in the dessert, only to see dirt for miles. In the time that we spent running, we crossed areas of dirt in which we saw stains of blood. That night we passed under a bridge, in a sewer tunnel, which smelled horribly. I can still taste the smell of the mossy water, suspended mid-air in it’s collection of waste. As we walked, my sister fell face-front into the sewer water and carried with her the lingering smell. Arriving onto a cemented road, we were all loaded onto the back of a truck and taken into San Diego, California. We woke up in the United States—showered and rinsed the dirt from our backs—our dreams enveloped by a nightmare and incarcerated by a wall. I had never realized until years later that as long as we remained in this country, we would be labeled criminals. We had entered this place in obscurity, ignoring the presence of a wall that screamed, stay out!