Behind Closed Fences

With just the touch of a pinky finger, Playas de Tijuana has been one of the main focal points where Latino families are able to connect from the U.S. side to the Mexican side. Loved ones schedule to gather and meet at International Friendship Park every weekend. This is when the park is most lively. Children run along the fence, street vendors walk the boardwalk selling fruits and shrimp kabob and kites are flown along the beach.

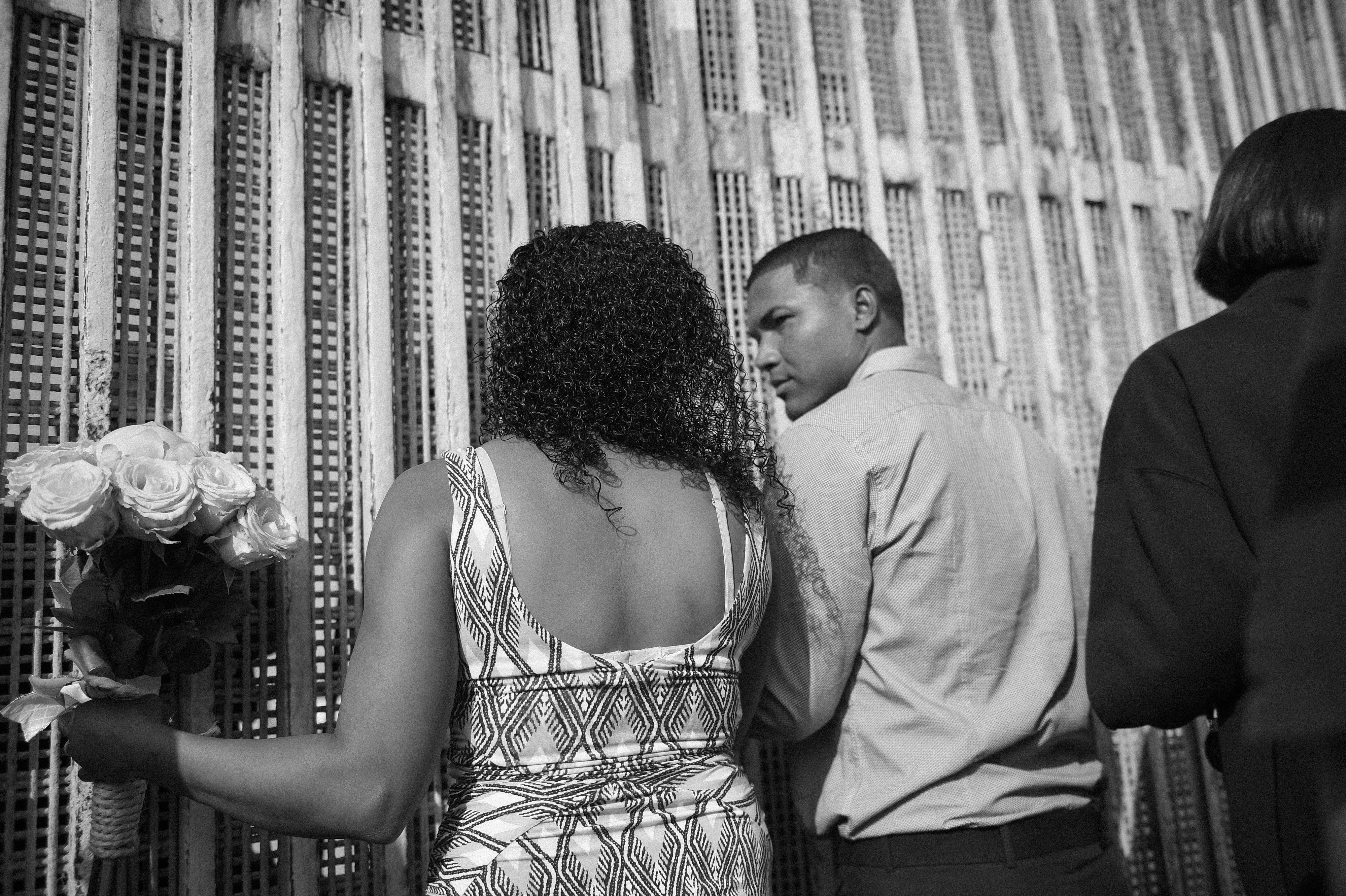

A Honduran couple married in front of the border fence, vows were exchanged in English by a pastor on the U.S. side, with only a silhouette visible. The metal fence is threaded tight with tiny openings. This is a celebration for Reynaldo Hernandez and Karla Lindo-Hernandez. The 27-year-old newly married couple had just received asylum in the U.S. after waiting almost a month. After the wedding ceremony, Lindo-Hernandez, who was visibly pregnant, broke down into tears of relief and joy.

This was just days before the Central American caravan had arrived. What loomed ahead was unimaginable, for some. “No one is prepared,” says Hugo Castro, director of Border Angeles, an all volunteer, non-profit advocacy group that works for “humane immigration reform,” especially with issues at the US-Mexican border.

The Pew Research Center indicates that over 1 million immigrants head to the U.S. each year. More than 500,000 people cross into Mexico every year, according to The UN Refugee UNHCR. This massive flow of people crossing into Mexico is mostly comprised of Central Americans who have one destination in mind: the U.S. border fence, where a new life awaits them. They are optimistic about their chances of receiving asylum in the U.S. But their optimism comes at the expense of immense odds.

Today, the U.S. has more immigrants than any other country in the world, accounting for 40 million. The U.S. and Tijuana border represents a new beginning for many Central American families who have trekked thousands of miles by foot, bus and infamous trains, such as “The Beast.” It is a surreal experience for many young Central Americans.

David, who wished not to disclose his last name, took “The Beast,” where stories of murder, death and kidnappings are a common occurrence. David, a 20-year-old Honduran left his homeland by himself for the two-month trek towards Tijuana, Mexico. “Most of us are young and escaping violence. We come here to work, not to create problems,” he said. “I saw two youngsters die on ‘The Beast’. One of them lost his leg and bled to death right in front of me.” That is only half the struggle David had to go through. At 8, David’s mom committed suicide while 8 months pregnant. “My father had a hard time dealing with things, so he became an alcoholic.”

There are many young Central Americans who share similar stories of confrontations with death amongst their loved ones back home. Those who risk their lives to make it to the frontera is only half the effort it will take to cross over the legal way. But it is a risk many are willing to take even if it means being smuggled across.

An unidentified woman from Guatemala showed the calluses on the soles of her feet before explaining her situation. She left her homeland with her 12-year-old daughter and expressed concerns over the long list of asylum seekers for the U.S. Now, she is currently waiting for a worker’s permit to stay in Mexico.

According to The Washington Post, 700 migrants decided to begin the same process, most of who are concerned for their children’s education. “The Mexican government offered educational opportunities for my daughter and that’s what matters. I want her to learn and get a good job,” the woman said.

There are still caravans expected to arrive at the crammed sports complex. It has turned into a tent city made up of 6,000 Central American refugees. There is a lack of both a sewage and warm water system. The bathroom stalls are outside and people usually head for the cold showers in the early hours of the day, when the air is cold and dry—whatever it takes to avoid the long lines.

People bathe as they face the looming border fence, only a dozen yards away. The portable bathrooms release a sewage stench throughout the sports complex and baby diapers overflow the trash bins. U.S. helicopters hover above the 6,000 Central Americans throughout all hours of the day and night, while Mexican Federal Police patrol the streets, a tactic of authoritative presence.

Oscar Roberto, 45, had to flee El Salvador after the 18th street gang put a gun to his head inside his home. “They robbed me of my home,” he says. Roberto, who had arrived to Tijuana on November 20, was a local street vendor who sold clothes in his community. He is strictly looking towards seeking asylum in the U.S. and not in Mexico. “This country is just as dangerous too. What I hope for is to have an opportunity to live and work in the U.S.,” he said.

For example, with the rise of newly elected right wing governments such as, Sebastián Piñera of Chile and Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil, governments in Central America mirror the political atmosphere that has taken shape after decades of conflict throughout the regions. Instability and corruption continues to rig economies, including Nicaragua’s sociopolitical system under the Daniel Ortega administration . In addition, amidst the influx of people fleeing their homeland, it was reported that Juan Antonio Hernández, the brother of Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández and a former congressman, was arrested in Miami on November 23. He is accused of collaborating with multiple criminal organizations in Honduras, Colombia and Mexico to smuggle tons of cocaine into the U.S.

“One can have a good life, work hard and have the unfortunate events of facing death,” Carrillo Garcia explained. The 24-year-old is from San Pedro Sula in Honduras, one of the most dangerous cities in the world. Where Garcia is from, the murder rate is 173 per 100,000 residents. He had no choice but to leave his two children and wife behind as he sought out the one-month journey to Tijuana. “Honduras is complicated. Life gets complicated when you see your loved ones die, also.”

The future is uncertain for the many Central Americans who are due to the treacherous conditions it took to get to Tijuana. They were met with tear gas, high police presence and discriminatory rhetoric on both sides. For now, the fences remain closed, despite their stories of struggle and pain.