Fresh air and clear blue skies stretch above. The sounds of birds chirping somewhere in the distance of the green fields are calming, but the barbed wire fences are a reminder that not long ago this place was once a nightmare for many.

It’s hard to imagine a time when dark clouds covered the skies and black snow drifted down to earth. The fences hummed with electricity that kept everyone inside.

Jerry Weiser will never forget the stories of his mother and the horror of the concentration camps that she was forced to bear.

“In order for you to understand where I’m coming from, I’ll have to start with my late mother’s story first,” Weiser said as he paced around the stage at the Sophia B. Clark Theater on May 9.

Weiser’s mother, Eva Gisela Pomeranz Weiser, was 19 when World War II broke out. Three months later, Eva went back home from college to find that her family was taken by German soldiers. She never saw her family again.

Being alone in a country that was invaded by Nazis pushed her to leave Poland and cross the border to Slovakia.

“Slovakia didn’t get invaded. Slovakia was a fascist government and in a lot of points, they agreed with the Germans,” Weiser said.

One of the rules implemented was that Jewish people can only work for other Jewish people. Several weeks after arriving to Slovakia, Eva eventually found work as a housemaid with the Engel family.

She started working for the family in a small town, but was soon forced to leave when neighbors started to ask questions about Eva’s citizenship status.

Fortunately, the first woman Eva worked for had a daughter and son-in-law looking for a housemaid in the capital city of Bratislava. The Engel’s had a very successful coffee business; they were very well known, not just in the city of Bratislava, but all over the world.

It wasn’t long after moving to Bratislava when Eva met Weiser’s father.

When they wanted to get married they realized they had several obstacles in their way if they ever wanted to do so legally.

“Both of them were not citizens of Slovakia, and on top of it in those days when you got your ID card they used to put your religion on [your ID] card. So, here you have two Polish people, not residents and Jews on top of it,” Weiser said.

Despite not being able to legally marry they stayed together, and in 1941 they welcomed their first child together.

Three months later, Weiser’s father was nowhere to be found. Eva looked for him everywhere, and eventually, one of Weiser’s father’s coworkers told her that he was taken by German soldiers. She never saw him again.

When Weiser was seven months old, his mother was forced to take all of their belongings and move to the ghetto.

They had to wear yellow Jewish stars on their person at all times. The living spaces in the ghetto were small and crowded; families, as many as six, had to squeeze into one room. There was very little food for everyone and some died on the street because of hunger.

The ghetto had tall brick walls and barbed wires around it, making it look more like a prison than a home for the Jewish community.

Not long after arriving, there were rumors that the Germans were going to take everyone from the ghetto and send them to a camp. Eva was barely able to feed her baby in the ghetto as it was. She knew the probability of being able to take care of him in a camp was very slim, especially since being able to take care of a baby in the ghetto was difficult.

With the help of a nurse, who went to the ghetto once every two weeks, Eva made an unbearable decision to smuggle her baby out of the ghetto.

“My mother didn’t have a choice and she said this to herself, ‘This will be the only chance that the baby is going to have to survive. He has a chance to survive,’” Weiser said.

There was no certainty that she would ever see her child again.

Before the nurse left Eva had one final request. She requested a letter be sent to the Engel family to let them know where Jerry was.

The nurse hid Jerry inside her medicine bag and they escaped the ghetto, and she took Jerry to the city church where they managed to keep him safe for a few weeks. Yet they needed to send him somewhere else since he was not safe in the church. German soldiers regularly checked homes and institutions, including the churches, to make sure they were not hiding any Jewish people.

Weiser explained, “I was sent with a farmer outside of the city. He was a God fearing gentleman, and very brave. He took me in and he hid me in his house for three and a half years.”

Not only was the farmer hiding Jerry from German soldiers, but he was also hiding him from neighbors that could report to the authorities. If the neighbors were to report that they found a Jewish person they would more than likely get a decent prize for finding a Jewish child.

Eva was taken out of the ghetto by the Nazis who took them to train tracks called, “Road of No Return.” Many Jews from the ghetto were squeezed into the wagons.

“There was hardly any air to breathe there. There was no food, there was no water, there was no privacy, there was nothing,” Weiser said.

It took 10 days for the people in Eva’s wagon to arrive at the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. Many died along the way.

“You’ll see on top of the gate [in Auschwitz-Birkenau] it says, ‘work will set you free,’ what work? 10,000 Jews were killed every day, 24 hours a day,” Weiser said.

Eva was now there, with the electric gates that could kill her if she touched it, and the horrible smells she couldn’t escape.

But she had one advantage that would keep her alive.

The Germans needed certain people, like interpreters, to help run the camp. Since Eva studied languages in college and spoke five different languages fluently, she was an obvious choice.

One advantage that came with being an interpreter, was that she was able to send postcards outside the camp. She wrote postcards to the Engel family and she wrote about Jerry, asking what happened to him. The German soldiers forced her to write all her postcards and information in German so they could read it and track it.

She sent four different postcards, but none ever left the camp.

“This was the propaganda act, they wanted to show the world that they had a post office in the camp,” Weiser said.

People were dying from hunger in the camp, at the hands of the guards, or from being picked to go into the chambers.

One day, Eva’s 18-year-old cousin forgot to put her shoes on before morning roll call. A German soldier saw her without her shoes on and put a bullet in her head right in front of the courtyard. The German soldiers would tell musicians to play their instruments as they ordered men and women to enter the gas chambers.

Weiser explained these details to an incredibly quiet crowd. Envisioning these haunting moments that his mother lived through could send shivers up your spine.

After three long years in Auschwitz the guards gave each woman of their choosing, including Eva, a whole loaf of bread on a cold winter morning.

This was not a sign of good fortune or that the guards were being lenient on them; each person with a loaf of bread was forced to start walking out of the camp.

They traveled on foot from Auschwitz, Poland to an all female camp in Germany known as Ravensbrück. The loaf of bread was all the food they were given to eat for the entire journey.

Only a third of them survived. They either died from the freezing cold weather, starvation, or from being shot in the head if they tried to rest at any point during the three weeks it took to arrive at the next camp.

“This was known as one of the worst camps of all the camps,” Weiser said.

The guards at this all women’s camp were much more cruel and treated the women worse than the men’s camps. When Eva arrived at Ravensbrück, she wrote a poem that described that she lost all faith in God and humanity.

In May of 1945, she was liberated from Ravensbrück by the Russian army. Quickly after being set free from the camps, she was sent to rehab in Sweden to heal from the emotional and physical damages that she endured in the two concentration camps.

When she was healthier, she was eager to reunite with her son.

She sent letters to the Engel family and to the nurse who smuggle Weiser out of the ghetto. She asked them to help her find her son and eventually got in contact with many people until she found out that he was in Slovakia.

Even after the war, Slovakia still had a strong anti-Jewish mentality and that combined with the harsh immigration restrictions in Sweden did not make it easy for Eva to see her son again.

After the war, the Christian farmer sent Weiser to live with another family called the Prissigens. They took Weiser in with open arms, and gave him a “sister” 10 years older than him. The Prissigens then baptized Jerry in their local church where they took him every Sunday.

Weiser still has his baptism certificate from Slovakia where they even gave him a new name: Euron.

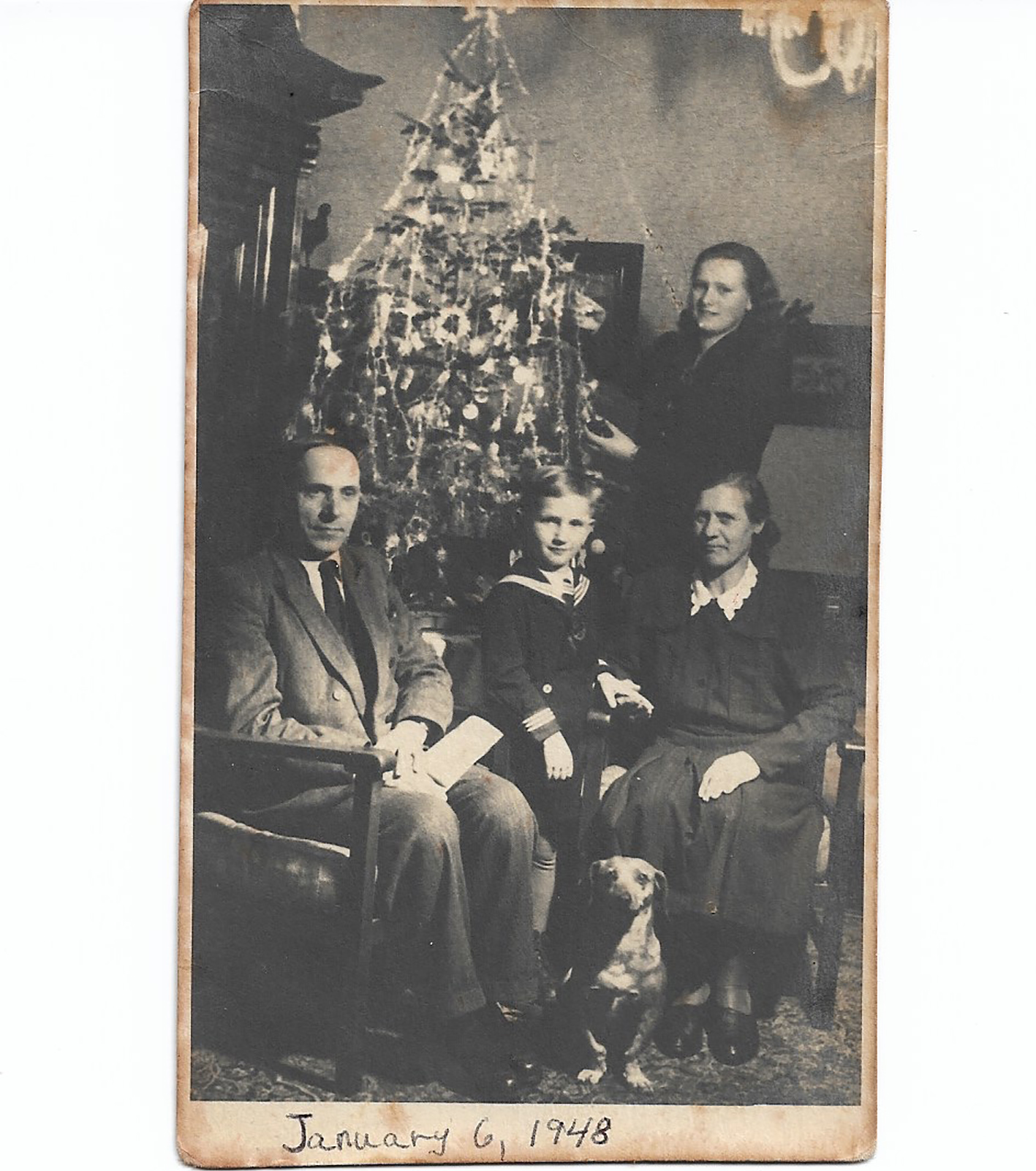

During the summers he would run around the backyard and pick cherries from the cherry tree. Weiser celebrated Christmas with them, and on one of those holidays, he received a gift of a sailor’s outfit.

“The Prissigen family never told me this was from my mother. I found out many years later,” Weiser said.

At one point, Weiser and the Prissigens were in Israel, when Eva found out that they were out of Slovakia she decided to sail over to Israel and be reunited with her son.

“Israel was under the British mandate, so they wouldn’t allow any Jewish immigrants to come to Israel. The British Navy turned the ship around and sent them to the Island of Cyprus,” Weiser added.

Eva arrived to her third and final concentration camp, but the camp would not stop her efforts to be reunited with her son. She managed to convince those who were running the camp to do two things: to let her get in contact with a Jewish Agency to get her son, and to let her leave the camp.

As Eva worked to reunite with her son, the Prissigen family loved Jerry as their own and even considered adopting him.

At seven years of age, there was a knock on the door from Rabbi Solomon Schonfeld, who was working with a Jewish Agency.

“His life calling was to save children. He saved over 3,000 children before the war, during the war, and after the war,” Weiser said,

He was one of those children.

The Rabbi told the Prissigens that Jerry’s mother was alive and that she wished to be reunited with her son. The Prissigens knew they needed to let him go, so with heavy hearts they gave Jerry to the Rabbi.

It was very confusing for Weiser at the time because the only family he had ever known was the Prissigens, but the rabbi took Weiser along with 148 other Jewish children on a long pilgrimage from Bratislava to Germany, Holland, Belgium and Ireland. In Ireland, all the children stayed in a very large castle.

The children would play sports and games all the time in the castle, and they were known as the Hide and Seek Children. Weiser was the youngest one in the group.

Nine months later, Eva and the Rabbi made arrangements for her to reunite with Weiser in Israel. Eva was finally liberated from the camp, so she could see her son.

“Finally, when I was eight years old, I was reunited with my mother in Israel,” Weiser said.

The audience in the Sophia B. Clark Theater clapped enthusiastically at that point of the story.

When the clapping died down, he began to speak calmly again. Weiser told the crowd that after his mother died he researched her life during the Holocaust, since she never wanted to talk about it.

As a grown man he went on a voyage of his own back to Germany. He visited every place that his mother was forced to go. Everywhere from the train tracks with the sign, “Road of No Return,” and the wagons that she was forced to squeeze into with so many other Jewish people. Then to Auschwitz-Birkenau which he described as looking like a “country club” when he went to visit it.

Finally he went back to the castle where he lived before being reunited with his mother, and several of the other children he lived with were also there for a small reunion.

Weiser gave one final statement to the crowd:

“I’m here, standing as a witness that [the Holocaust] happened. Now that you have heard my story, you are probably going to tell it to somebody else. You became a witness too. This is why it is so important to stand here today to tell my story.”

Barbara Mortkowitz • Feb 11, 2021 at 12:45 pm

I hope one day to be able to read Eve’s poems.