In the Armenian language, “Odar” means “foreigner,” “outsider,” “other.”

Jason Perez, Drone Imaging and Photography Professor, brings an outsider’s perspective of Armenia to the Diana Berger Art Gallery through his exhibit entitled “Odar.” The showcase is comprised of 10 years of multimedia imagery that captures the travels of Perez throughout the war-torn country.

“Odar,” which opened to the public on Oct. 17, has been a deeply personal body of work for the L.A. based artist and media entrepreneur. Perez has always been intrigued by people, their past and how humans have changed their landscapes throughout the dawn of time.

After attending the ArtCenter College of Design, Perez figured out that he had a passion for telling visual stories. After making a name for himself as a photographer, Perez discovered his interest in exploring, seeing how people lived and learning about different cultures and what makes them tick. This was when his personal body of work began to expand.

“This camera can take me around the world, and I can just constantly be capturing people and cultures and how they relate to their environment,” Perez said. “Every time I pick up the camera—those are the things I think about—how people relate to their environment.”

After a trip to Armenia, he completely immersed himself within the culture.

Perez, who is Mexican-American, has a half-Armenian son and was initially motivated to preserve and safeguard the cultural legacy of Armenia on behalf of his son. He began reading, learning and discovering more about Armenia and the surrounding regions. Throughout his journeys, he reflected on his own origins of growing up in America.

“There was always this soul-searching thing throughout this work,” Perez said.

While in Armenia, hearing the term “Odar,” as if he was the outsider, was unsettling at first. In hindsight, Perez believes that the current stigmas held in America, of who belongs and who doesn’t, is why the Armenian expression seemed offensive to him at first. Through understanding the language and culture, he realized that there is no other way to explain it. To the people of Armenia, the word is used as a term of endearment.

Through time, his Armenian friends eventually told him that he was one of them—he was the same as them.

“But I will always be the ‘Odar,’ even when we come home and we’re here—we’re still the ‘Odar,’” Perez said with significant realization.

Perez’s family lineage goes back five generations in south Texas, near the American/Mexican border. One day his family’s farm was on Mexican soil, and the next day the farm was apart of the Texas annexation and entered the United States Union.

“Growing up, for my family, the Americans never wanted us. They called us Mexicans but the Mexicans never wanted us, because they called us Americans,” Perez said. “So we were always ‘others,’ and we always have been ‘others’ as a Chicano nation.”

Throughout interactions with the people of Armenia, Perez was able to recognize the close bonds that tied them together as a people. According to Perez, no matter where you live within the world, if you have 10 percent of the heritage in your blood, you are considered full Armenian in the eyes of the culture.

In America, the debate goes on of who does and doesn’t belong. Yet in Armenia, they embrace their own. No matter where they are in the world, they’re embraced as family.

Growing up during the Cold War era, Perez was always curious about countries that were affected by the Soviet Union and the Iron Curtain period. He began to speak to the people of Armenia, hearing first-hand accounts of what it was like to be under Soviet rule and their experience during the collapse of communism. He was intrigued as to how people can come back from these moments. He reminds us that we, as Americans, don’t have these same struggles.

“Our difficulties [here in America] are that we can’t get our lattes right,” Perez said sarcastically.

Perez describes Armenia as a country that faces its past through ancient monuments, which serve as a constant reminder of its heritage. Armenia’s history runs deep; it is considered to be a sacred biblical land and the first country in the world that fully embraced Christianity. However, the country has braved centuries of darkness, as it has been ruled by many dynasties, faced a genocide that killed 1.5 million people, and survived a 70-year Soviet rule. Yet despite the amount of brainwashing the country has endured, the mighty people of Armenia have maintained a resilient culture that is rich in spirit.

“Armenia is made up of a juxtaposition between this biblical land and the [Soviet] military,” Perez said. “I love seeing how a place changes, and the people change, but the …. actual landscape never does.”

Perez expanded from personal work to cultural preservation through donating his time to the Armenian youth through the TUMO Center for Creative Technologies. TUMO is a non-profit organization in which students receive free education and can learn a variety of different subjects that range from photography, web design, animation, music and anything else in the digital world of media.

Perez’s journey through Armenia found a new purpose through his work with TUMO. He began to teach Armenian students how to operate and use digital imaging technology to capture cultural and ancestral locations. He wanted the students he trained to be able to carry the torch forward and digitize it further for future generations.

“They can continue on the fight. It’s not my fight, it’s their fight,” Perez said. “It’s their country.”

Kandyce Fierro, a 26-year-old Mt. SAC student and military veteran, was invited by Perez to spend six weeks in Armenia to help tutor students at TUMO. Fierro and a small group of Mt. SAC students went to Armenia to teach students how to historically map their locations to preserve them forever. The group used drones and 360 cameras to capture terrestrial and aerial landscapes. They scanned various historical interiors and exteriors through laser scanners and multispectral cameras.

Fierro found it important to help maintain this history and culture, which has repeatedly been ripped from underneath the feet of the Armenian people.

“The kids out there are so smart, you’re with them for 5-10 minutes, and they’re teaching you a little bit of something. I received a lot from the students that I taught out there,” Fierro said.

Perez hopes that anyone who goes to see the “Odar” exhibit will be able to understand the Armenian way of life and find some sort of appreciation for the culture.

Raylene Lopez, sign language interpreter at Mt. SAC through the Accessibility Resource Centers for Students, took the first Photo 50, named Drone Basic Still and Motion Camera Operator, class offered through Mt. SAC. She took the class for professional development and found interest in the program. Perez invited her to travel to Armenia to work with TUMO to continue the historical mapping project.

It was the first time she stepped outside the country, and she immediately felt the culture shock. She fondly remembers the people of Armenia as kind, unique and welcoming.

Lopez remembers one specific day abroad in which they planned to see the beautiful waterfalls of Armenia. They stopped and asked a random family for directions who were in the middle of having an afternoon picnic. Lopez recalls how welcoming the family was and how they invited them to eat with them and partake in an abundance of food and hospitality.

“It was so different than anything I was ever used to—that would never happen here,” Lopez said.

It was after a trip with TUMO that former Mt. SAC Dean of Arts, Sue Long, and Exhibit Curator Fatemah Burnes encouraged Perez to showcase his work to the world. The thought of putting an exhibit together left Perez with hesitation and unease because he saw his time in Armenia as profoundly personal. After some convincing, he committed to the exhibit, and it took over a year to put together. From that—a labor of love—called “Odar” came to life.

The work itself is made up of three types of imagery, including digital and drone photography and 360 photogrammetry, which takes pictures of an object stitch by stitch to make an exact 3D replica. Within the gallery is a virtual reality section, in which visitors can strap on goggles and walk through the halls and steps of some the most sacred Armenian churches and institutions.

Perez is inspired by various artists, including one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century, Robert Frank, who was known for his documentarian style of social commentary. Perez recognized that the photographers he admires the most were continually questioning what was happening in society, and this concept resonated with him.

Perez captures the connection between people and their environment through the work displayed in “Odar.” He exposes viewers to the community of Armenia and how each hand helps the next. He communicates this through his use of still photos. Perez displays images of religious figures and the monasteries that house them, architectural landscapes that were built centuries ago and the everyday life of the Armenian shepherd that stands against the backdrop of the rolling hills.

The black and white photos appear to represent Armenia’s deep-rooted history and traditionalism. While brightly colored images seem to represent the country as it stands today, moving forward, out of the dark past that once plagued it.

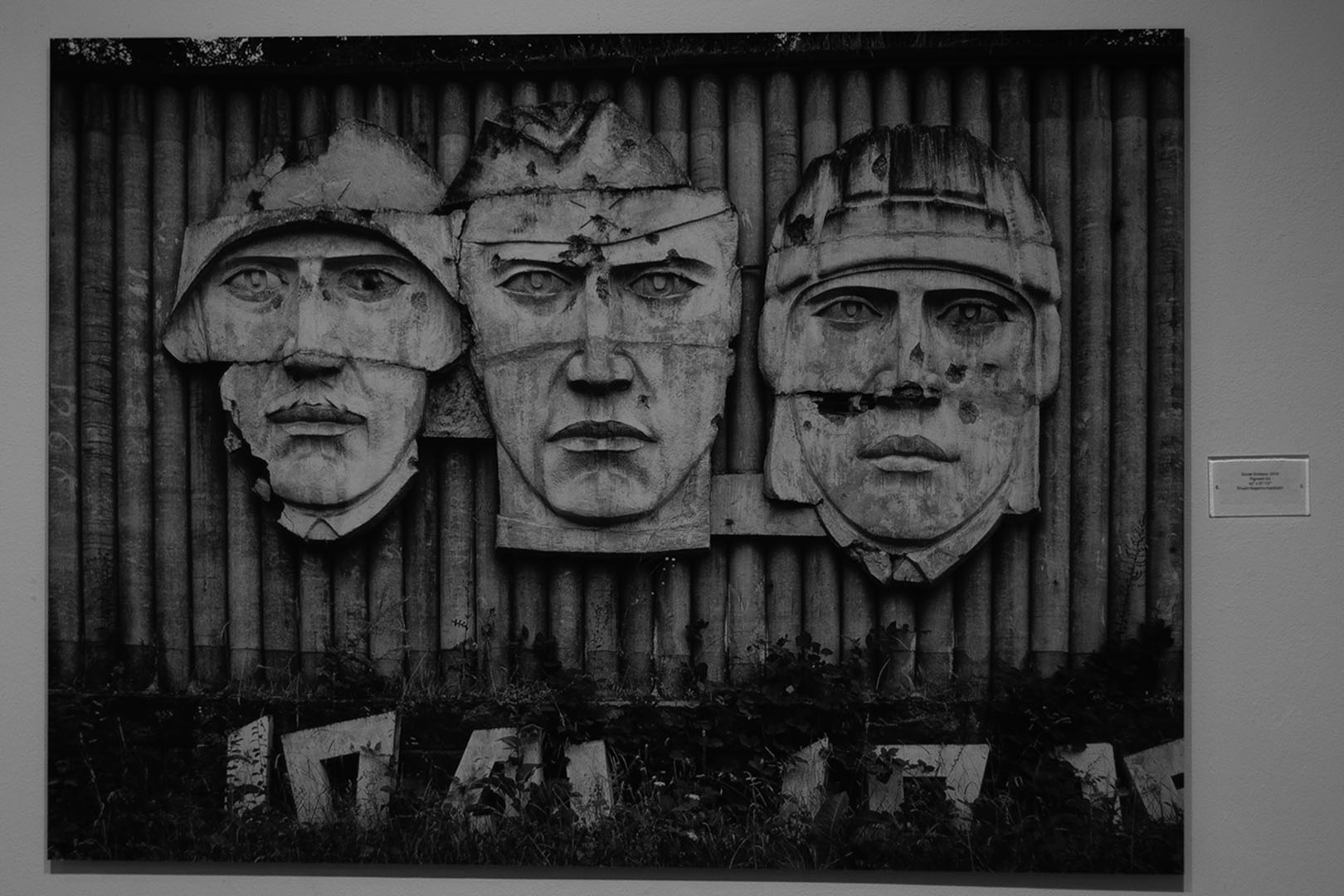

Perez’s photography of the disputed land of Artsakh displays the contrast between war and beauty. He displays imagery of highway murals of once Soviet soldiers now riddled with bullet holes. Fallen statues of Lenin that lay on its side and demolished tanks abandoned by the side of a river bend are left as historical artifacts of the communism that once ruled the country. Showing the remnants of war and how the people of Armenia keep moving on, despite the country’s past atrocities.

The time and dedication of this project proved to be challenging. Still, Perez hopes visitors can leave the gallery with gratitude and thankfulness.

“An appreciation for what you have and an appreciation for what you don’t have,” Perez said.

Cultural preservation is a vital process for Perez.

“This whole show shows a part of what we have to do and what we want to do,” Perez added.

“Not just for Armenia, but I think it’s important for all of us, this [project] might be Armenia, but this is the world’s history. This is … our history. If it’s old, we need to protect it. Because it’s constantly being trampled on and destroyed. It goes beyond what we do in Armenia, it has to happen globally, for all of us,” Perez said.

Perez has been vocal that this project is not about him. It’s for Armenia, and it’s for the dozens involved that helped bring “Odar” to life.

The students that came along for this journey are in awe to see the exhibit firsthand. They were thankful for the time they spent in Armenia and will cherish the memories for years to come.

Fierro said that she wishes to revisit Armenia someday in hopes to make her own impact.

“I miss Armenia very much, and I hope that I get a chance to visit again. That’s definitely a part of my bucket list, I want to go back. Like Jay [Perez] and do something to be a little bit more than be an outsider, you know … to be able to bring this perspective to other people and open their eyes up a little bit,” she said.

For Perez, “Odar” is more than a personal project or labor of love—it was what he was called to do. After six trips to Armenia, which lasted up to seven weeks at a time, he feels that the exhibit has finally brought closure to his time in Armenia.

“This was something that I had to do…sometimes it’s hard to make that separation. Between the things that you have to do and the things that you want to do … and sometimes the things you have to do takes care of the things you want to do.” Perez added. “But in this beautiful world, we think we can do both, but sometimes that’s not the case.”

Luckily for us and Armenia, Perez was able to capture the best of both worlds.

“Odar” runs until Dec. 5 and is free to the public. For location and hours, please visit the Mt. SAC Art Gallery page.