Mt. SAC has violated the law by refusing to release documents and by not placing incidents on the crime log within the time frame mandated by law.

These laws include the California Public Records Act and the Clery Act, which both refer to the disclosure and release of particular records.

The Clery Act is federally mandated legislation that requires colleges and universities to collect crime reports from campus security authorities. The act was created in 1990 after a student named Jeanne Clery was raped and murdered in a residence hall at Lehigh University in 1986. The act requires that crimes on campus and surrounding applicable areas be reported and that preventative programs, safety measures, crime logs and fire logs be maintained.

The California Public Records Act requires that government records be made accessible to the public upon request, unless otherwise exempted by law. Once a request has been made, the agency must determine within 10 days whether the request may be disclosed and promptly notify the requester of this determination.

If special circumstances occur, they may extend this window to 14 days.

Without posting any reasons for extensions, Mt. SAC’s Police and Campus Safety department has ignored numerous informal emails requesting reports on incidents that have occurred on campus from SAC.Media News Editor Joshua Sanchez.

Current Sports Editor and then Managing Editor Brigette Lugo made multiple attempts to contact Campus Police Chief Michael C. Williams by leaving him voicemails and emails in order to receive the incident report. She also contacted the department’s administrative specialist, Stephanie Bolechowski, who referred Lugo to another individual.

Ignoring these requests is not an acceptable response to requests asking for the reports under the law. The Clery Act fine can cost the college up to $54,789 per violation, and failure to comply with the California Public Records Act could have cost the college from $1,000 to $5,000 had Assembly Bill 1479 strengthened the act.

Even without a fine, the college would still be in violation of the PRA if a court finds that the college “knowingly and willfully” failed to respond to a request for records, unreasonably delayed providing the records, improperly added a fee that exceeded the cost of duplicating the records or otherwise did not “act in good faith to comply with this chapter.”

The college has to make the crime log for the most recent 60-day period available to the public, and any portion of the log older than 60 days available within two business days of a request for inspection, according to U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 34, Code 668.46, Section F, Paragraph 5 of the Clery Act.

The college does make the daily crime log accessible to the campus, but the incident reports from the crime log have to be redacted to be viewed. Only one individual on campus, Chief Michael Williams, has the authority to redact information, according to the campus police and public safety department.

Aside from the 60-day period, the incident reports must be made available within two business days of an initial incident report being made to the department or campus security authority, according to U.S. Code 1092, Section F, Paragraph 3, Subsection B.

They were not.

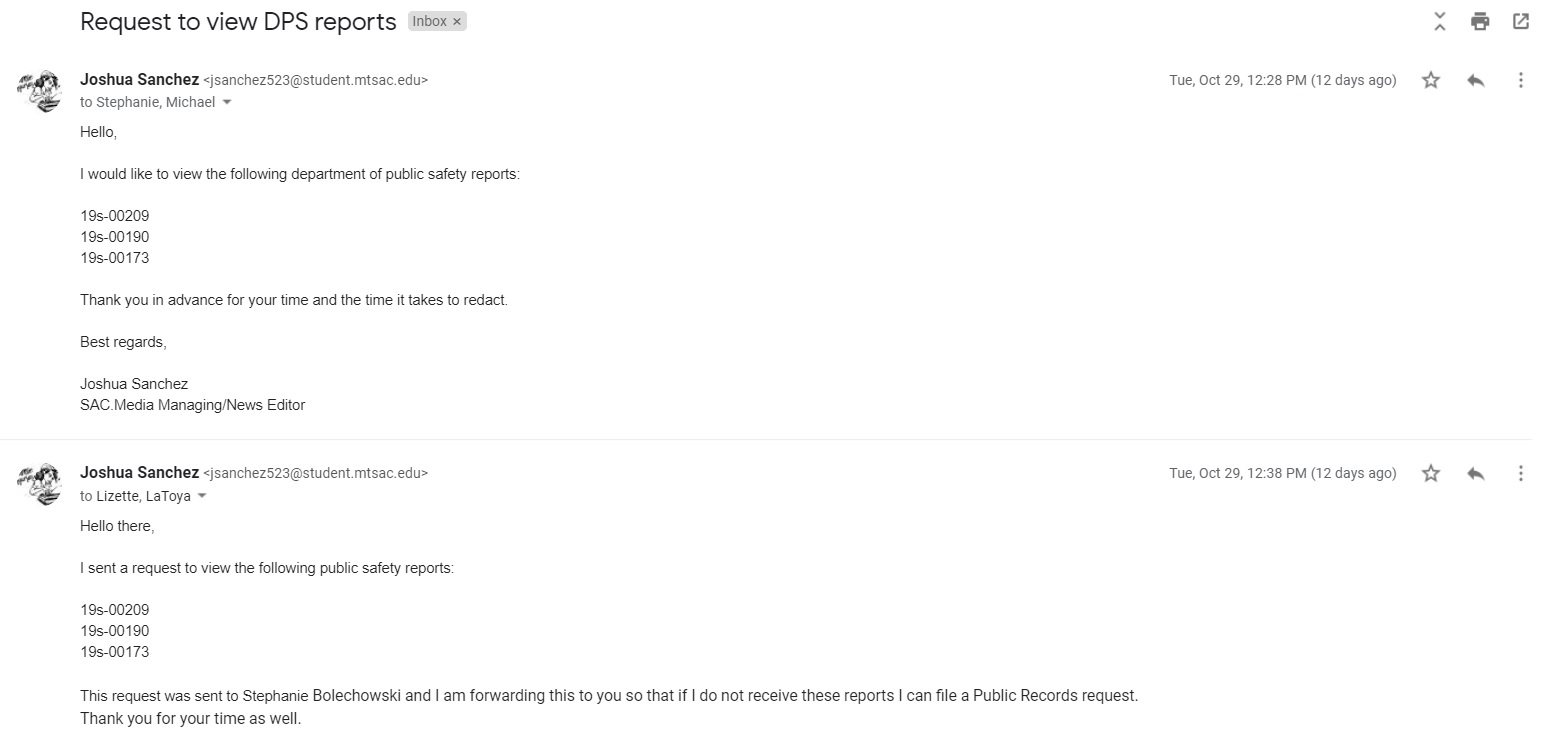

Sanchez has sent four requests for incident reports from public safety and has sent follow up emails as well. These emails went without a response.

The latest request asked for reports from three invasion of privacy incidents and was made on Oct. 29 at 12:28 p.m. This request was sent to public safety and forwarded to human resources, which has processed other requests for financial records that did not involve public safety.

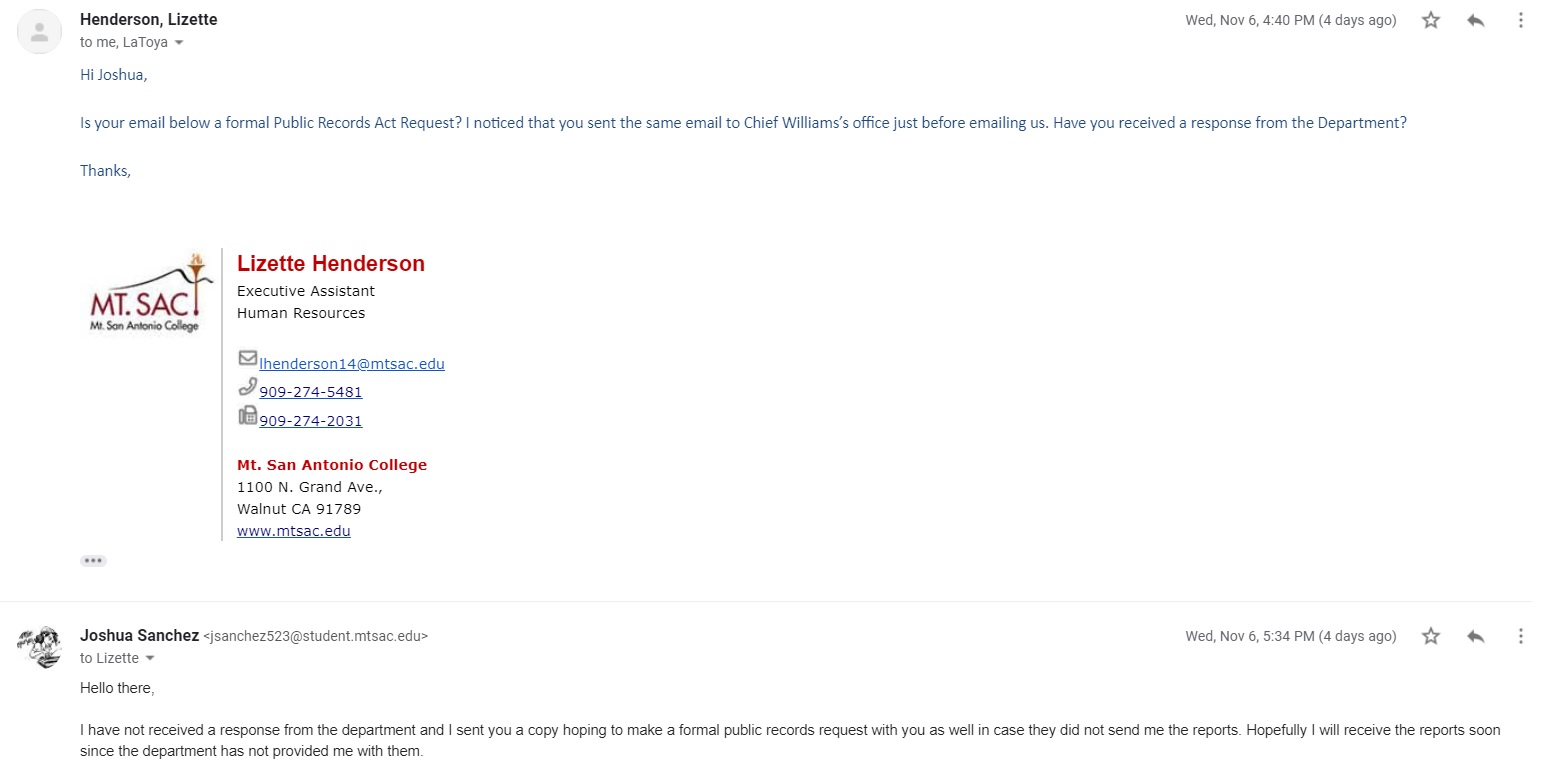

Human Resources Executive Assistant Lizette Henderson was the only one to respond on Nov. 6 at 4:40 p.m. The response asked if the request was a formal records request and whether or not public safety had gotten back to Sanchez.

Sanchez replied at 5:34 p.m. that he had not received a response from the department and that the email to human resources was intended as a formal PRA request since the department had not provided the information.

Prior to this, Sanchez had requested incident reports from the police and public safety department alone.

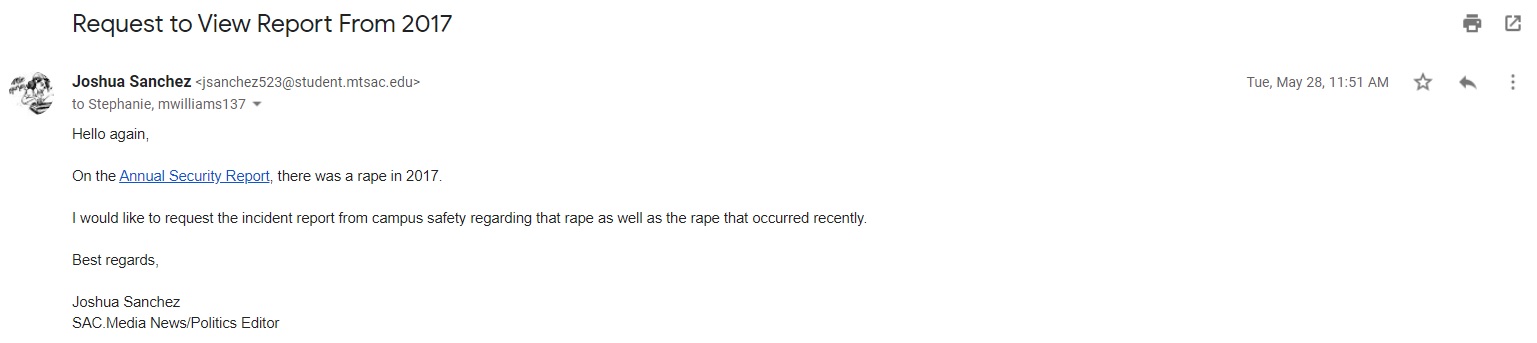

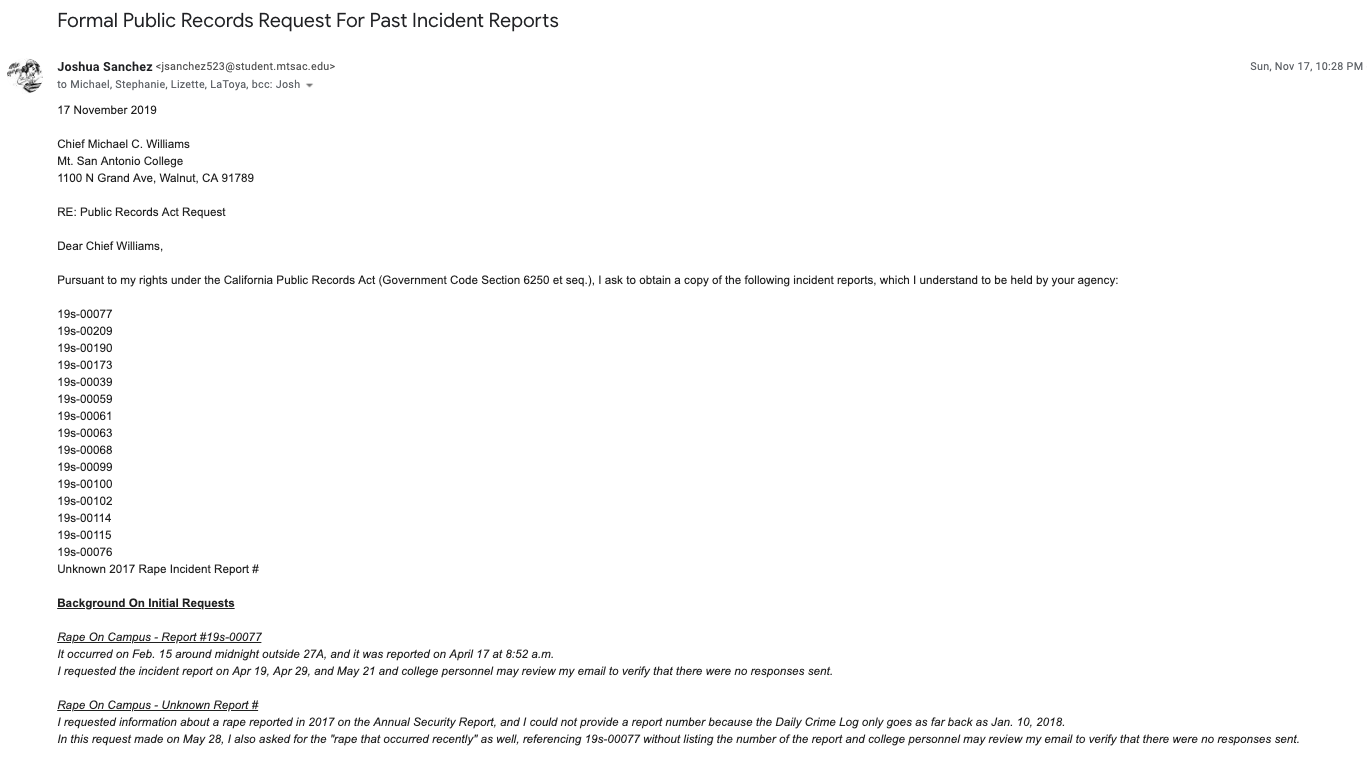

On May 28 at 11:51 a.m., Sanchez requested the incident report of a rape reported on the 2017 annual security report, and this email received no response.

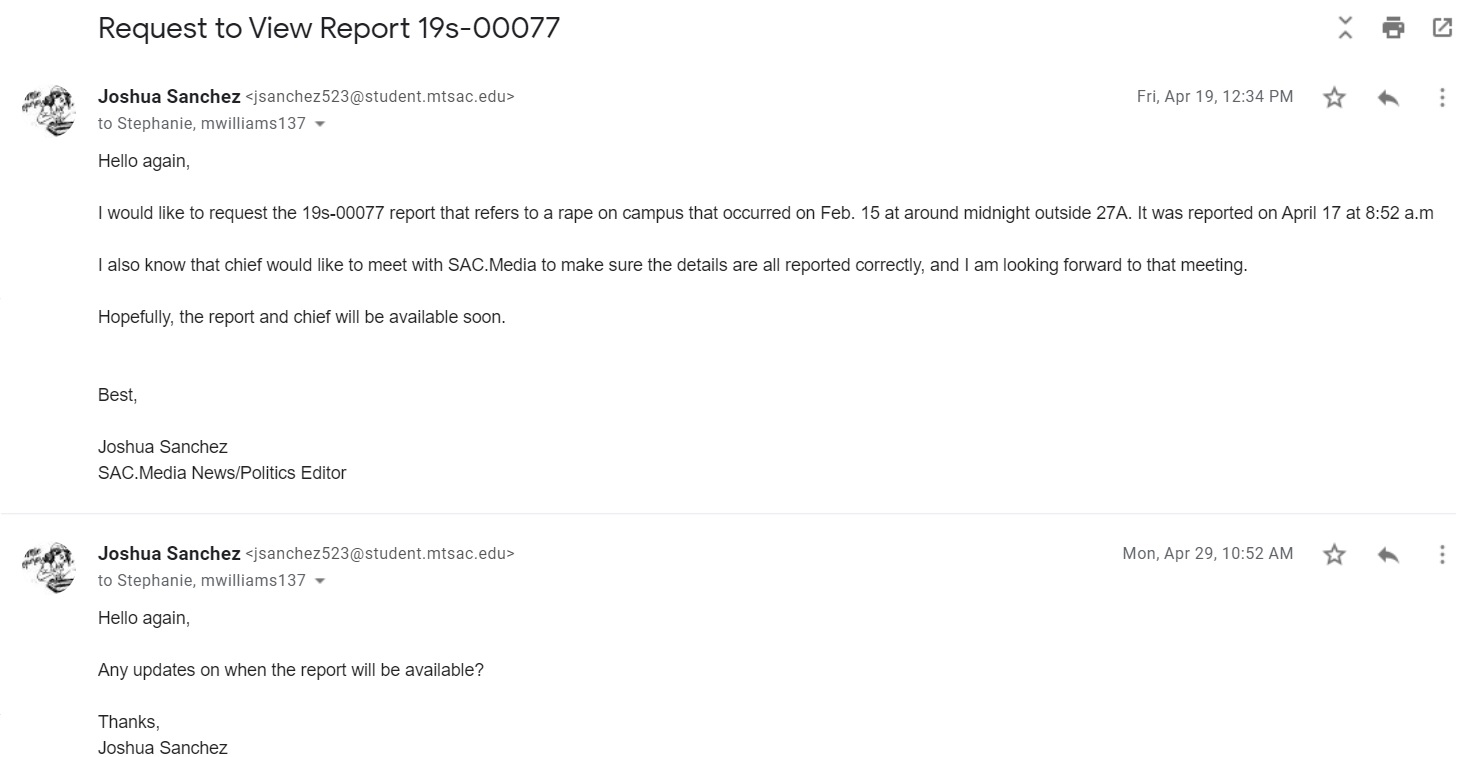

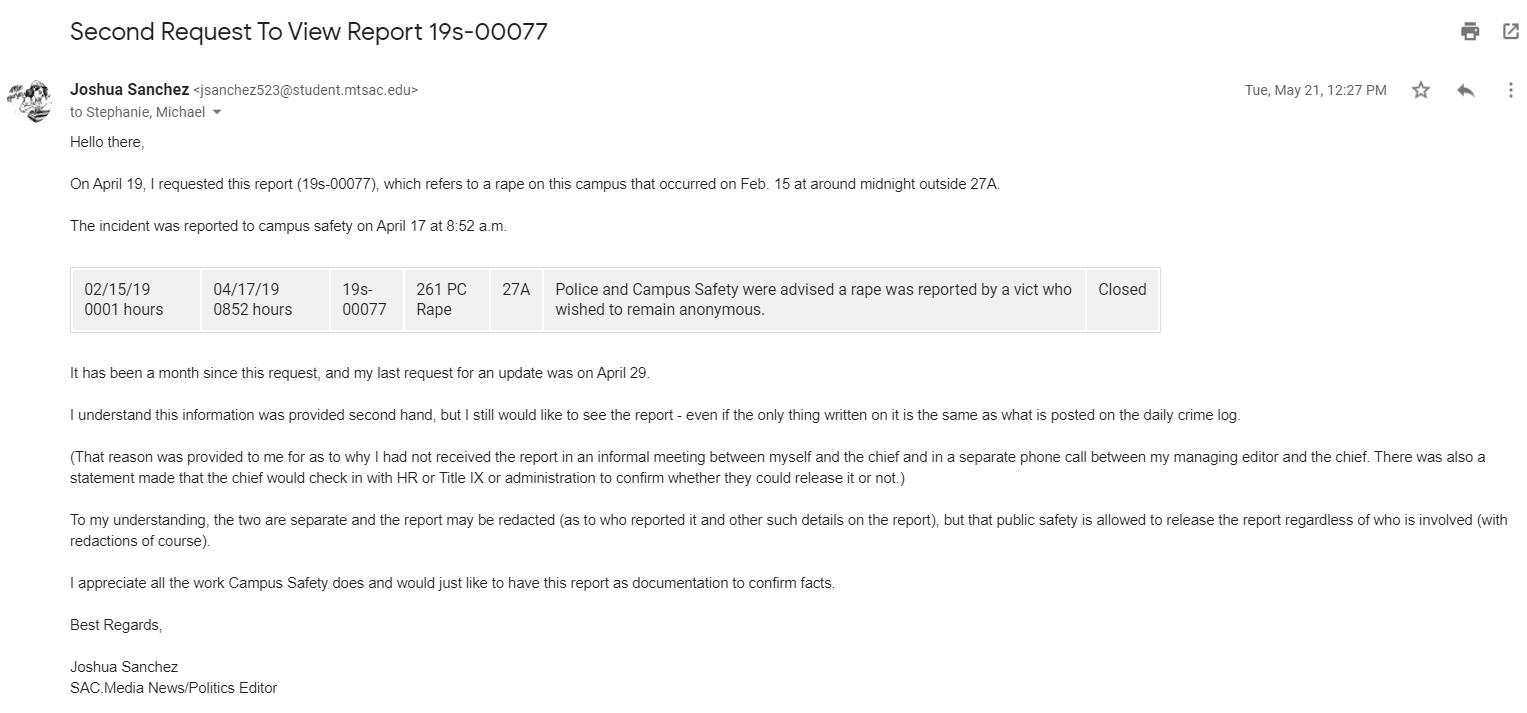

Sanchez requested a report on April 19 at 12:34 p.m. and a follow up request on April 29, 10:52 a.m. Both emails went unanswered.

On May 21 at 12:27 p.m., another request was made for the same report, and this request also received no response.

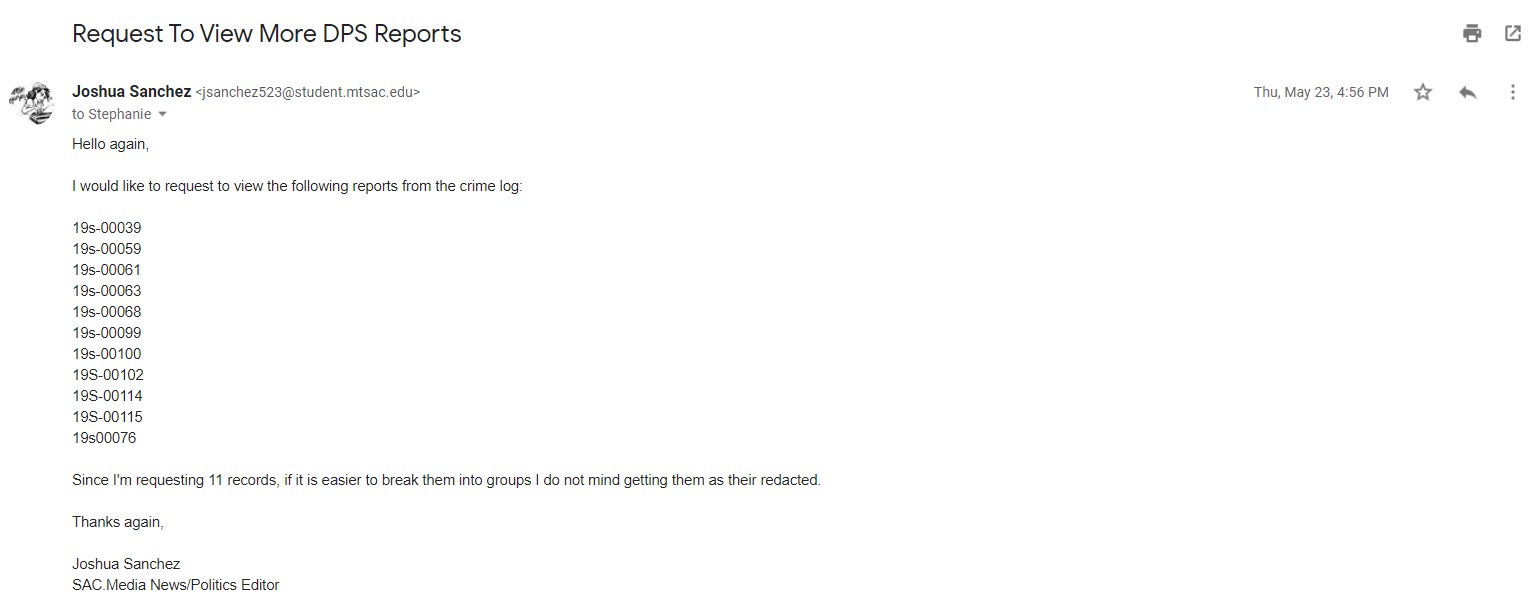

Another request was made on May 23, at 4:56 p.m. for further incident reports, and there was no response.

It was not always this way.

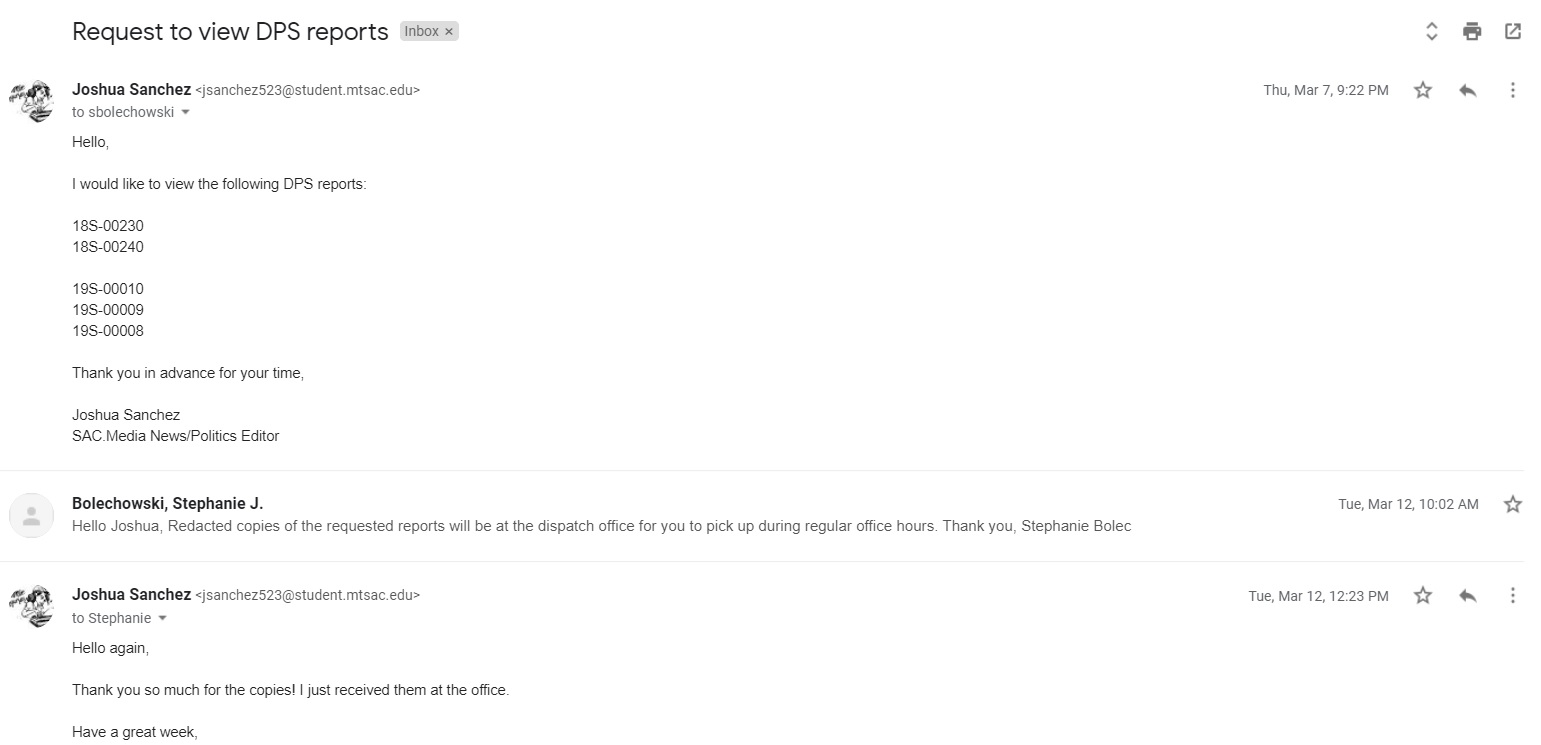

Sanchez was able to receive incident reports from a request made on March 7 at 9:22 p.m. for reports regarding incidents in parking lots.

The redacted reports were received on March 12 at 10:02 a.m. to be picked up during regular office hours.

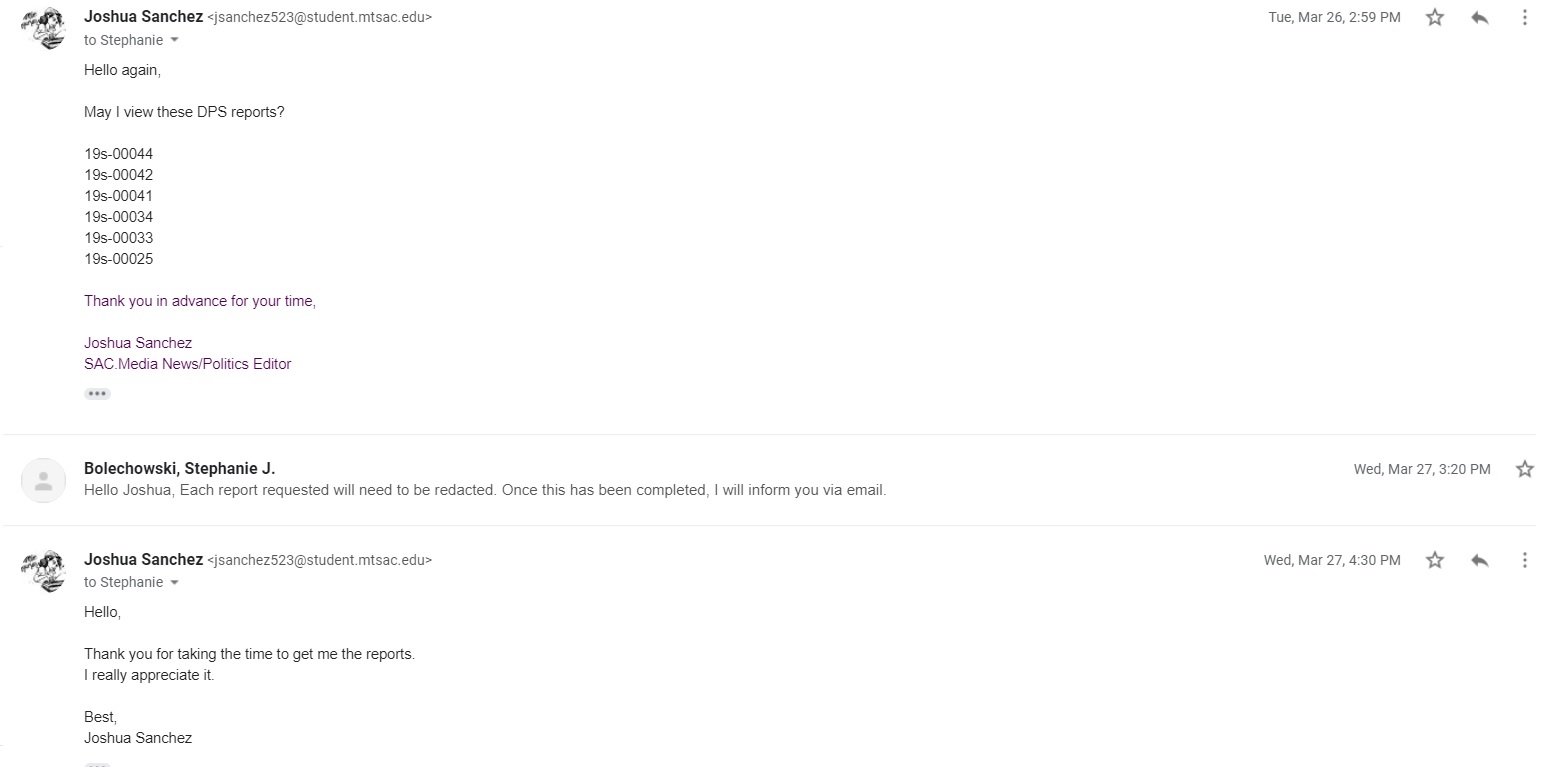

Sanchez also requested incident reports of further parking lot incidents on March 26 at 2:59 p.m. and received a response on March 27 at 3:20 p.m. stating that once each report was redacted, Sanchez will be informed via email.

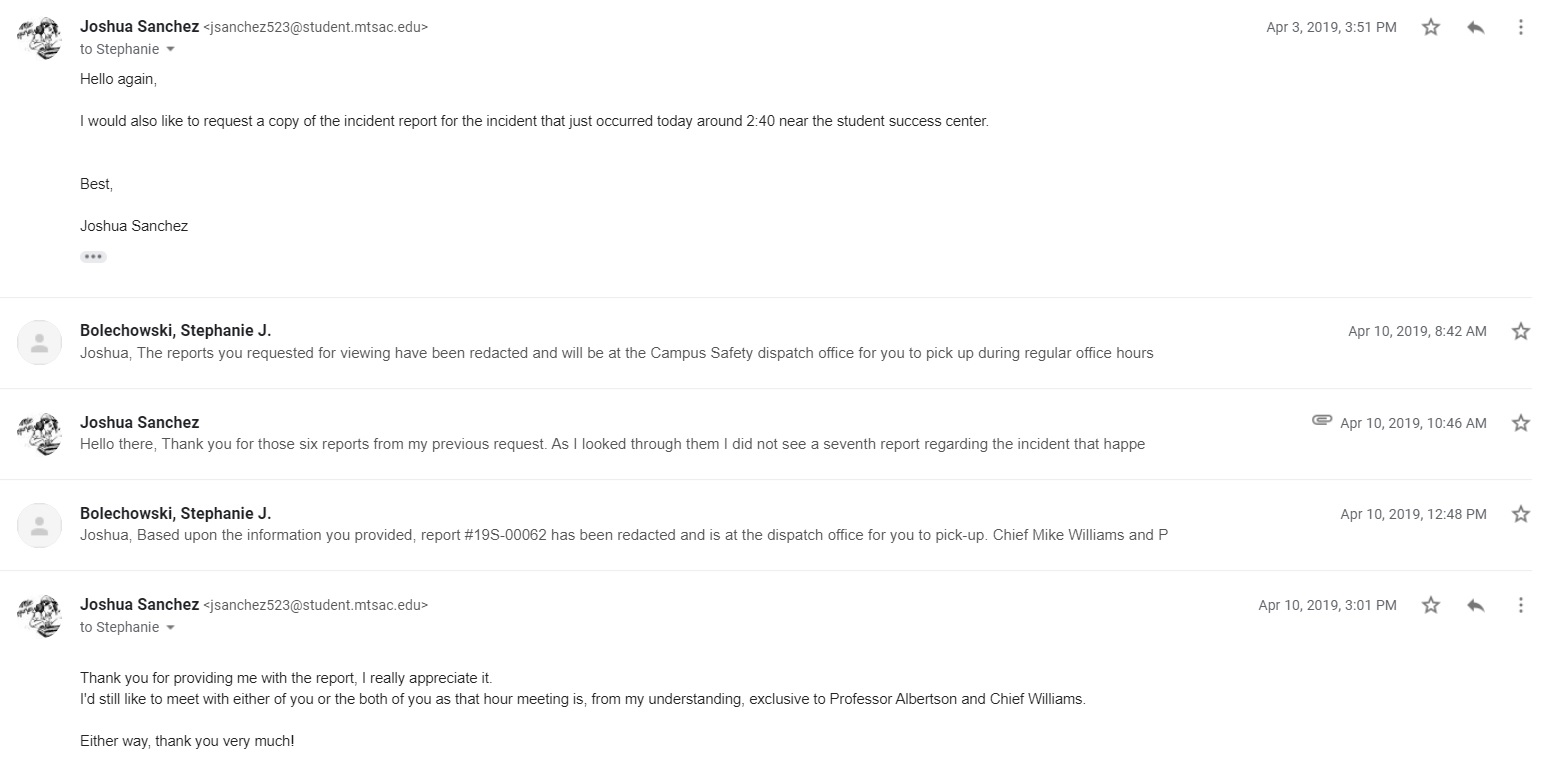

On April 3 at 3:51 p.m., Sanchez sent another email asking for a new incident report, which was labeled as student misconduct instead of a crime. A response was received stating that the requested reports were available on April 10 at 8:42 a.m.

Those redacted reports did not include the April 3 incident, which was labeled as student misconduct because the individual involved was filming the behinds of clothed females.

“We only put crimes on the Crime Log,” Williams wrote to Sanchez after Sanchez asked why the April 3 incident was not found on the crime log. “We assign incident numbers to non criminal incidents.”

Sanchez was told that the matter would have been considered a crime had the individual involved filmed under the clothes and invaded personal privacy.

A follow up email was sent to describe all particulars known about the April 3 incident on April 10 at 10:46 a.m., and a response was received the same day at 12:48 p.m. telling Sanchez the report was available for pickup.

The original coverage of the story was hindered by not having all of the information available when it broke, but after the report was released, the update clarified information.

Similarly, while campus safety has not released the reports for the three latest invasions of privacy, the marketing department posted a campus-wide alert less than an hour after the story went up.

This is not the first time that Mt. SAC has been in violation of the Clery Act. SAC.Media published an editorial regarding how the college has violated the law in 2015, and another one about the police department being instructed not to talk to the student press in April of this year.

The second editorial came after a rape was reported on campus and Mt. SAC Title IX and Equal Employment Opportunities Investigations Manager Ryan Wilson said the assailant who committed the crime was not a threat to the campus. Williams said that he had as much information as was reported on the crime log for the Feb. 15 listing.

The crime log stated that “Police and Campus Safety were advised a rape was reported by a vict who wished to remain anonymous,” but the chief did not release a copy of the incident report, despite requests made to him and Bolechowski on April 19, April 29 and May 21. The Public Safety Office had 10 days to produce the report, according to the California Public Records Act. This means they are in violation.

Senior Director of Programs at the Clery Center, Laura Egan, has also told SAC.Media that the rape incident needed to be reported on the date of the occurrence, Feb. 15, and on the date it was reported to campus safety, April 17, in order to comply with the Clery Act.

Previously in 2015, a piece ran stating that the college violated the Clery Act by not logging a college crime report of a rape allegation made by Aarefah Mosavi after she had went to public safety. Later on, it was reported that an incident report was filed and that the students could pick it up, which contradicted what the police chief at the time had said.

“The people that were here at the time erroneously did not include it so it’s not in the current public safety crime report, it’s not correctly captured. We realized that last week when all this was coming to a head that previous people who were in charge here — for whatever reason and I don’t know why — didn’t mark. There should be a one where it says December of 2013 because that’s when, that’s not when we became aware of it, that’s when it was reported to have occurred,” Chief Dan Wilson said at the time.

The next year, in 2016, Public Safety provided SAC.Media staff members with the crime log, and a piece ran stating that the college was no longer in violation of the Clery Act.

Similar issues from the past are now back, as campus safety has not provided several incident reports to SAC.Media.

***

After multiple attempts by the staff to contact Williams, Journalism Professor and Student Media Adviser Toni Albertson was able to get in contact with Williams.

Albertson said that Williams cited FERPA and told her that the incident reports related to the sexual assault do not have to be released and that her students were wrong in the belief that they had to be released. Albertson said that Williams also told her that he has been studying the Clery Act for the past 18 months, and that she told Williams he was incorrect about the matter and that she advised her students to contact the Student Press Law Center.

After the phone call, Albertson sent Williams a copy of the laws regarding the laws regarding the release of incident reports.

On the Student Press Law Center website, under the frequently asked questions section about freedom of information, it states that all incident reports must be disclosed.

All colleges — public and private — are subject to the federal Clery Act, which requires them to maintain logs disclosing the “what, where and when” of serious reported crimes. In almost all states, a public college (and sometimes a private one, if its officers exercise arrest powers) must disclose “incident reports” that give a more detailed narrative of the investigator’s observations. And remember that federal student privacy laws do not apply to police reports.

While the Clery Act only requires the daily crime log to be reported and updated, the California Public Records Act requires the college to release the incident reports it collects.

A formal public records act request using a letter generator was also sent on Nov. 17, which outlined all previous requests sent by Sanchez and requested them again from campus safety and human resources. This formal request was sent in case the college administration determines that all past requests were not “official” requests. This request must be addressed within 10 days, unless an exemption to extend the deadline 14 more days is provided in response.

In a second call between Albertson and Williams, Sanchez was present.

Williams said that the formal request made on Nov. 17 was the right way to go and that Sanchez should call him on Nov. 27 for an update on the status of the reports. Albertson once again clarified that the CPRA required the release of the records, and that she understood the records will be redacted.

In a call on Nov. 27 between Williams and Sanchez, Williams said records would be ready by Wednesday, but did not specify which records or how many.

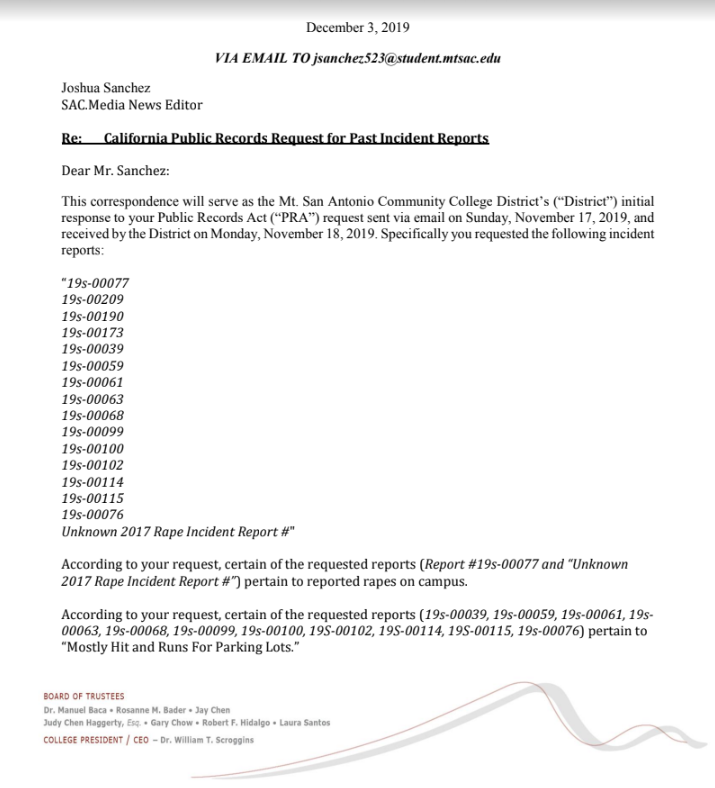

On Dec. 3, the day before Sanchez was to pick up the records, he received an email stating that the deadline would be extended by Equal Employment Opportunity Programs Director and Title IX Coordinator Sokha Song in response to his formal request.

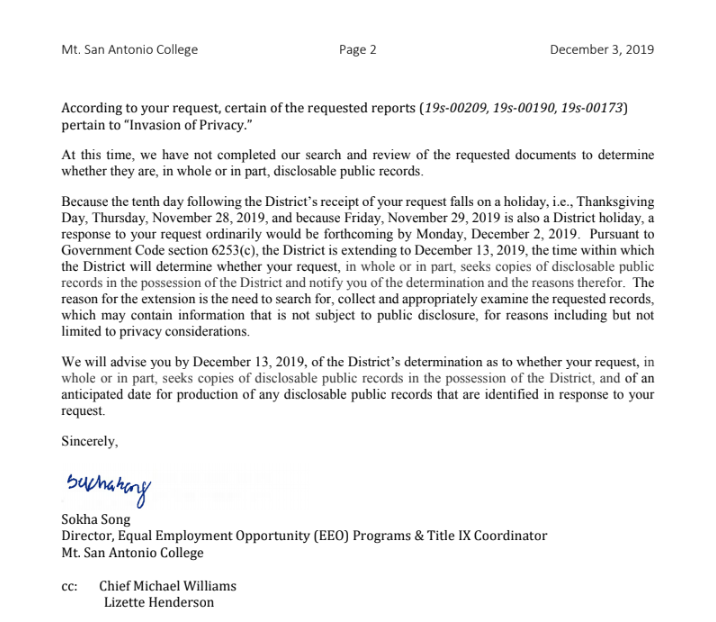

The email stated that the tenth day following the district’s receipt of the request fell on Thanksgiving that the response would “ordinarily be forthcoming by Monday, Dec. 2, 2019” but added that the district will advise Sanchez whether his request “in whole or in part, seeks copies of disclosable public records in the possession of the district” by Dec. 13.

This email was sent a day later than required under the PRA because it was sent on Tuesday, Dec. 3, where the first day after the holidays was on Monday, Dec. 2.

His email was later disabled on Dec. 6, and Sanchez had to provide documentation that he was an active student for the IT help desk to enable his email on Dec. 10, which was after he spoke with their desk to request his email be reinstated on Dec. 9. One respondent at the IT help desk said Sanchez was one of 700 students who had their emails disabled and that they had not seen anything similar at Mt. SAC.

It is unknown whether the college had tried to send the records to Sanchez during the time period his email account was down.

SPLC Staff Attorney Sommer Ingram Dean told Sanchez that if the college does not provide these records, the last recourse is to take the college to court. Dean also said she would look into more options regarding incident reports and that she would look through opinions of the attorney general, as some states have the attorney general handle issues regarding the PRA.

The SPLC website also states that a letter should be sent to advise the agency that they are violating the CPRA and to set a date for a lawsuit if the agency fails to respond because the CPRA does not “presume that delay is denial.”

—–

Update: Feb. 12, 6:15 p.m.:

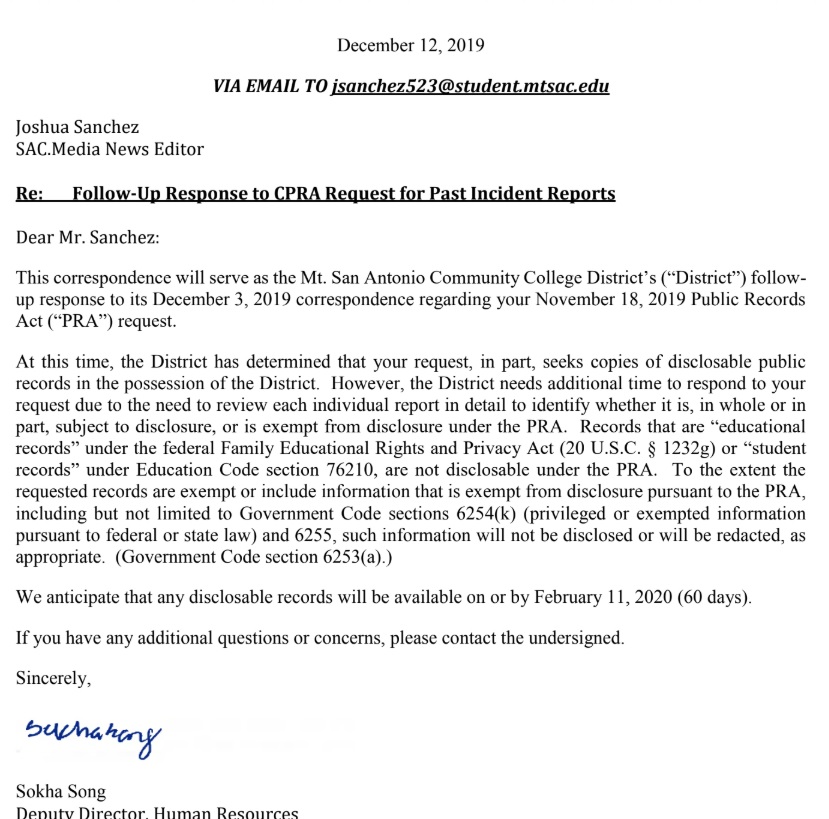

After the piece was written, another letter from Henderson and signed by Song was received on Dec. 12. This letter stated that the records would be made available in 60 days adding that they would be ready on or by Feb. 11.

Five days after receiving this correspondence, Sanchez’s student email was disabled again on Dec. 17 for an unknown amount of hours before being enabled again on the same day by the IT help desk before the campus was to go on break. It is unknown why the emails were disabled for either instance at this time.

No update was received on Feb. 11 and Sanchez went down to the office of Campus Safety the following day in person to request an update regarding the records. Chief Williams had stepped out before Sanchez had arrived and Sanchez ended up speaking to Sgt. Paul Miller at around 4:30 p.m. before sending Miller a forward of the original request and a follow up email with all the relevant information around 5 p.m. Miller told Sanchez that he would talk to Williams when he came in on Feb. 13 in order to provide Sanchez with an update as at this time there was no correspondence regarding the request.

Sanchez then received a response from Henderson on Feb. 12 with another letter from Song at around 5:30 p.m. and it is unknown at this time if Miller expedited the process.

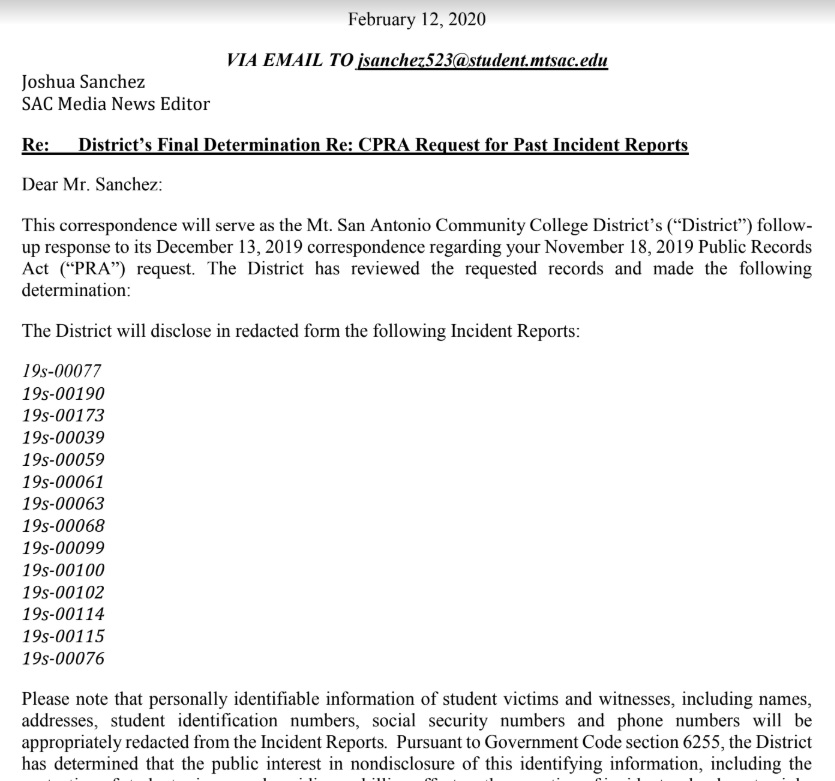

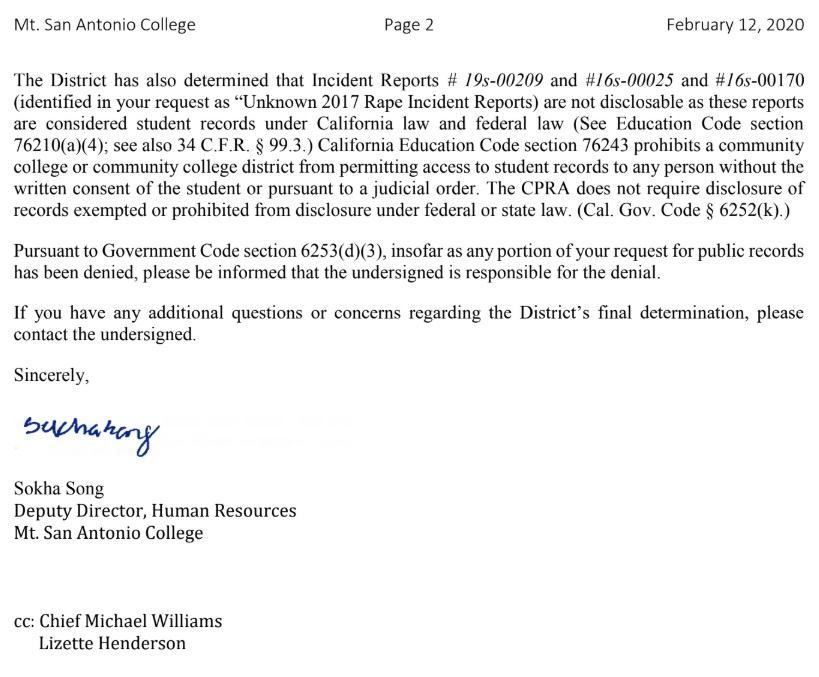

This letter was labeled as the district’s final determination regarding the PRA request and it extended the deadline to Feb. 25. The letter also included the exemption of three records while releasing the others that were requested.

The District has also determined that Incident Reports # 19s-00209 and #16s-00025 and #16s-00170 (identified in your request as “Unknown 2017 Rape Incident Reports) are not disclosable as these reports are considered student records under California law and federal law (See Education Code section 76210(a)(4); see also 34 C.F.R. § 99.3.) California Education Code section 76243 prohibits a community college or community college district from permitting access to student records to any person without the written consent of the student or pursuant to a judicial order. The CPRA does not require disclosure of records exempted or prohibited from disclosure under federal or state law. (Cal. Gov. Code § 6252(k).)

At the time of writing, the reports have not been released.

Update: Feb. 20, 12:45 p.m.

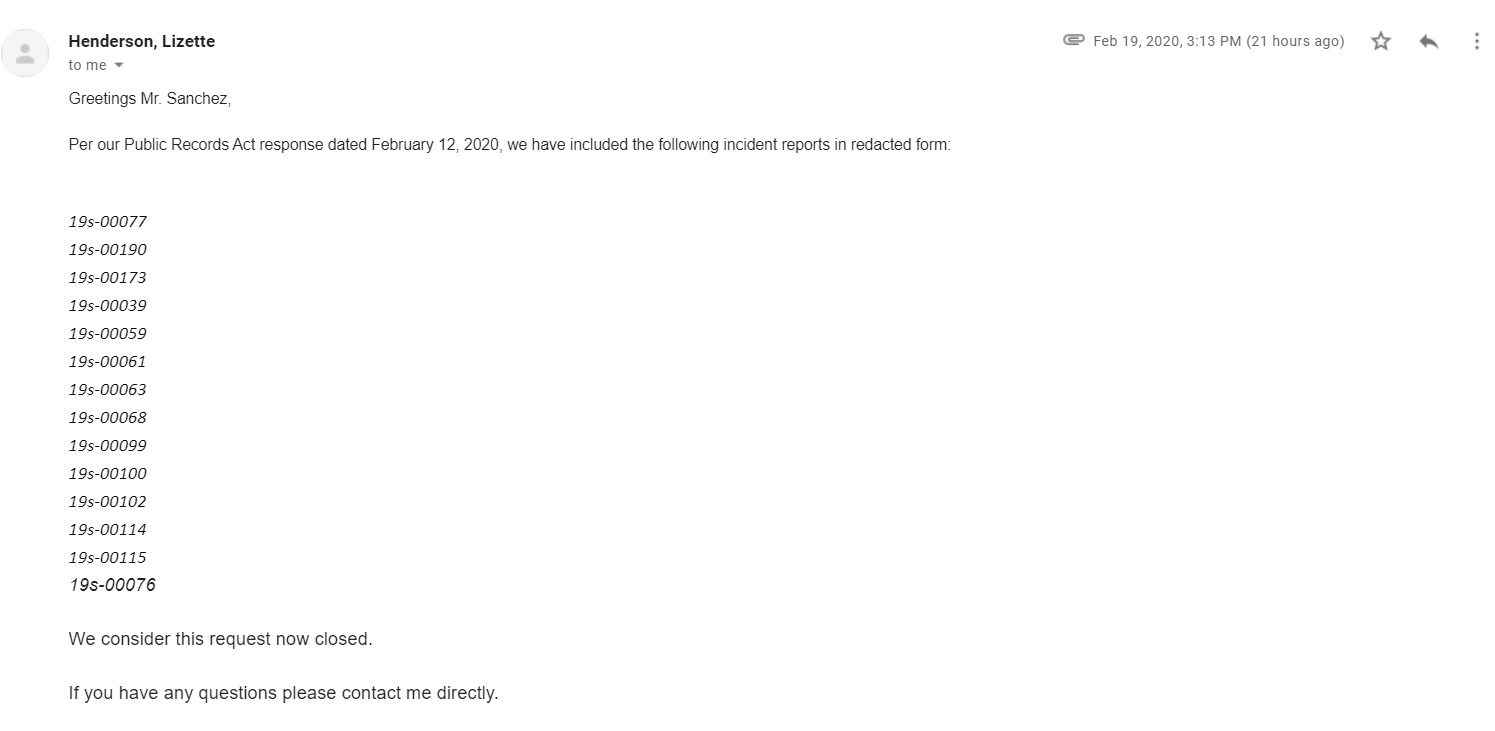

After being told by Miller that the chief said the reports would be handled by HR, Sanchez waited to receive the reports until Feb. 19 at 3:13 p.m. when Henderson sent Sanchez a digital version of the following reports: 19s-00077, 19s-00190, 19s-00173, 19s-00039, 19s-00059, 19s-00061, 19s-00063, 19s-00068, 19s-00099, 19s-00100, 19s-00102, 19s-00114, 19s-00115, 19s-00076 in two batches of PDF files.

Henderson has closed the request and Sanchez will be looking into why the three reports were considered “student records.”

Update: Feb. 20, 1:00 p.m.:

Headline has been changed from “Mt. SAC Still To Release Incident Reports” to “Mt. SAC Releases All But Three Reports” and the subhead has been changed from “By failing to distribute reports and refusing to answer emails, public safety is stopping the ability of the student press to report on incidents” to “After a lengthy struggle to receive reports, three have been classified as student records.”

The rest of the article has not been changed aside from adding the update(s).

As more information is made available this article will be updated.