Unidentified figures wearing white coveralls, white gloves and faceless black masks walk onto a dark stage. At moments, these figures appear to be headless. As they march onto the scene like ultramodern soldiers, they carry a mysterious box that is carefully placed on a black table. The front panel of the box is removed and gently placed on the floor below. The lights turn on. Inside the box is an encased head. A head without a body that stares blankly towards the audience.

“Headspace: Radical Thinking Inside a Box” is the latest play from the Mt. SAC theater department, which ran Feb. 11 to 13 at the studio theater.

The synopsis of the play surrounds “nine monologues each delivered by a disembodied head trapped inside a box.” The play is directed by Richard Strand, professor of theater, and is based on the book “Monologues for Headspace Theatre: Radical Thinking Inside a Box” by author and playwright Michael Bigelow Dixon.

This play hits close to home for Professor Strand, who is also a well-established playwright and whose work has premiered at several stage theaters around the globe. He submitted four monologues to Dixon, and two of them were selected for the book’s publication.

Strand—who is retiring after 20 years of service at the end of the spring semester—had the novel idea to bring the production to the college theater department.

“I didn’t even conceive of me producing it until the published book came out,” Strand said. “I thought, ‘Oh heck, there’s enough material here to do an evening.'”

The idea was fresh, out of the box—so to speak—and had never been done before.

“I don’t know anything else that’s like this … I wasn’t confident that it would even work,” Strand said. “That was part of the attraction too. Trying to figure how you build the box and how do you get light inside of the box. So, the challenge and the newness of it appealed to me.”

He selected nine of the 27 monologues from the book, including the two that he wrote and developed, and began casting for the production. He set out to cast the “best of the best” actors, as the play would restrict the actors of all physical movement.

Casting began in December, and rehearsals and pre-production started the first day of the winter session. Roughly 30 students showed up to the audition; however, nine were selected for the 90-minute play.

With casting out of the way, the creative challenges began to settle. A play that revolves entirely around a single actor speaking to the audience and telling a story inside the confines of a small box was a difficult task to manage at first.

“I had trouble figuring out even how to rehearse it because so much of what we do got taken away from us on this show,” Strand said. “Blocking is a big apart of creating a show, and movement is a big part of how you approach a play. That’s something that got taken away from the actor, they have to rely on their heads.”

Through the use of wooden crates, plastic and metal boxes and hours of rehearsals, Strand succeeded in his quest to bring this unconventional production to the stage.

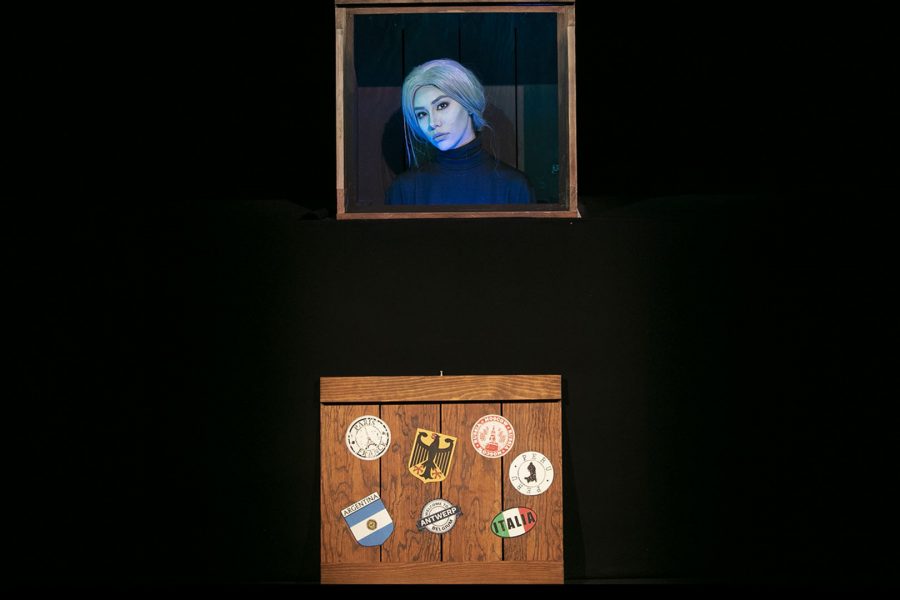

Through its writing style and the actors’ ability to express emotions through tone and facial mannerisms, “The Wig Mannequin,” written by the play’s director, stands out among the production. Sabrina Meza plays a mannequin head who tells the audience about an encounter with a strange man that walks by her in a department store and asks the off-putting question—“How you doing, Red?”

As a mannequin, she never had to think before; she never gave much thought to how she was actually doing. The idea alone gnaws away at her. So with all of the idle thoughts going through her head, she comes up with a plan to kill the man when she sees him next. She doesn’t know how or when, but what she does have is time. Time to think and plan it all out.

The writing is witty and playful, and Meza plays the character exceptionally well. She plays the part of a flawless mannequin whose insecurities and over-analysis are bubbling at the surface. Each word spoken marries well with every eye roll, piercing stare and intended frown.

―

The monologues selected for the performance of “Headspace” are thoughtful and subjective, while carrying light-hearted tones at moments.

Some monologues are straightforward in meaning and cunning in approach. “L’Inconnue,” written by playwright Cristina Luzárraga, centers around the fabled statue, the Unknown Woman of the Seine. The renowned bust of an unidentified woman from the late 1800s, its face was used as a death mask, and her image became a popular artistic fixture within literary works of art.

“L’Inconnue,” played by Natalie Grace Lambert—who does a hell of a French accent—speaks to the audience of her origins and the historic theories surrounding her mysterious death. She tells of the authors who described her face, and how a statue of her head came to settle in an encased box.

She sharply points out, with a sense of exhaustion, that her origins and true self is neither here nor there in the grand scheme of it all.

“I was and am everything—and nothing. I never lived,” the unbodied figure says. “I exist here for when you need me. I speak every language. I fit every story.”

This is the theme of the eclectic monologues of “Headspace.”

Origin stories of how they became separated from their body. Contemplation of the past and present. Endless thoughts of their overall purpose. And through it all, the concept works impeccably on the theater stage.

Through the use of abstract ideas and ambiguity, the play puts the characters at the forefront, creating an intimate setting that calls the attention of the audience.

―

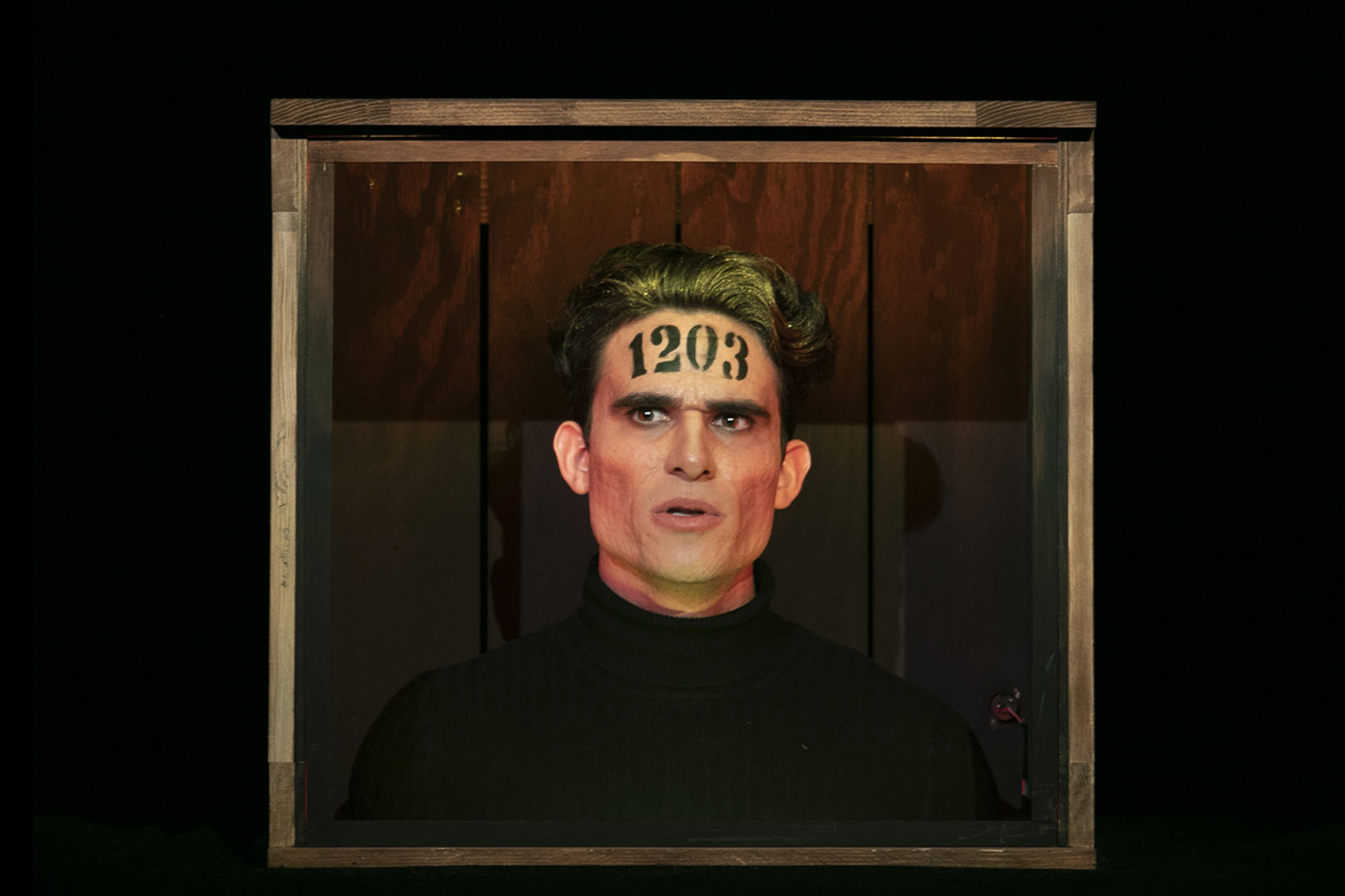

“1203,” written by Strand himself, is a significant act that encapsulates the viewer. The head in this box is described as a “revolutionary man,” played by Anthony Rodriguez, with the numbers 1203 tattooed across his forehead. The character is convinced his name is 1203, and he’s trapped in a box that sits on a shelf in some dark warehouse.

Through catching a glimpse of his own reflection, and through the process of elimination, he comes to believe he is not alone. He speaks out to what he believes is a neighboring head in a box named 1204, and spends the entire monologue pleading for a response. He wants to start a revolt; he wants validation that he is not alone. He craves human connection—if only for the sake of his sanity so that he can rid himself of his loneliness.

The number of lines each actor has to remember is remarkable. And their ability to connect with the character and with the audience makes for a unique experience. The performances throughout the play genuinely capture the acting capacity of each member of the cast.

―

The monologue “Dolly,” written by playwright Scott Dixon, is based on the character from the “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” television special. We are introduced to Dolly, the ragdoll, played by Malia Haines. She is decorated with a reddish yarn-like head of hair, freckled cheeks and enough makeup on her face to make a drag queen jealous.

She awakens at the noise of someone—possibly the doll’s owner—walking through the room, ignoring her as she sits eagerly in the box. Dolly reminisces about her heyday on the television special and recalls her time in the spotlight. She’s peppy, extremely chatty and full of energy. Yet throughout the monologue, we see glimpses into Dolly’s loneliness and her attempts at understanding why she feels disconnected at times. Dolly snaps in and out of optimism and cheerfulness, yet she can’t shake this feeling of separation. She craves attention and someone to talk to.

Although her voice is lively and energetic at times, you can sense her confusion and isolation as she speaks to the audience. You can’t help but feel for the character.

“But I’m wondering now if there’s only so much time you can be in here before something starts to happen to you,” Dolly said. “Because that feeling of separation? It’s not going away to tell you the truth. But nothing has changed, so it must be me. All in my head.”

―

“Headspace” is an experience that is all in the head. These boundless series of thoughts and emotions is what the play succeeds in capturing.

These moments hit the viewer with a stir of emotions. When everything else is stripped away, we get to witness the inner workings of the human psyche. A psyche of despair, loneliness, helplessness and existentialism lightly sprinkled with bits of humor and satire. We see the character’s thoughts, perceptions and desires. There are no other distractions. It’s just the actor and the audience.

Through profound writing, the right tone of voice and the individual microexpressions, it all leads the viewer to the window of the character’s soul. In the end, the viewer is left to wonder—what’s next?

Ironically enough, the heads trapped in the box search for those very same answers.