In the heart of Los Angeles is a sound that has taken the city by storm. In the world of mariachi is a vast source of knowledge and culture. It is a sound that allows people to connect to a heritage that almost seems out of grasp.

Mariachi is a party like no other; bringing joy to listeners of all cultures, a sound that makes listeners feel all types of emotions.

But the life of a mariachi is not about alcohol and music, but rather hard work and dedication to their craft of bringing enjoyment to their audience.

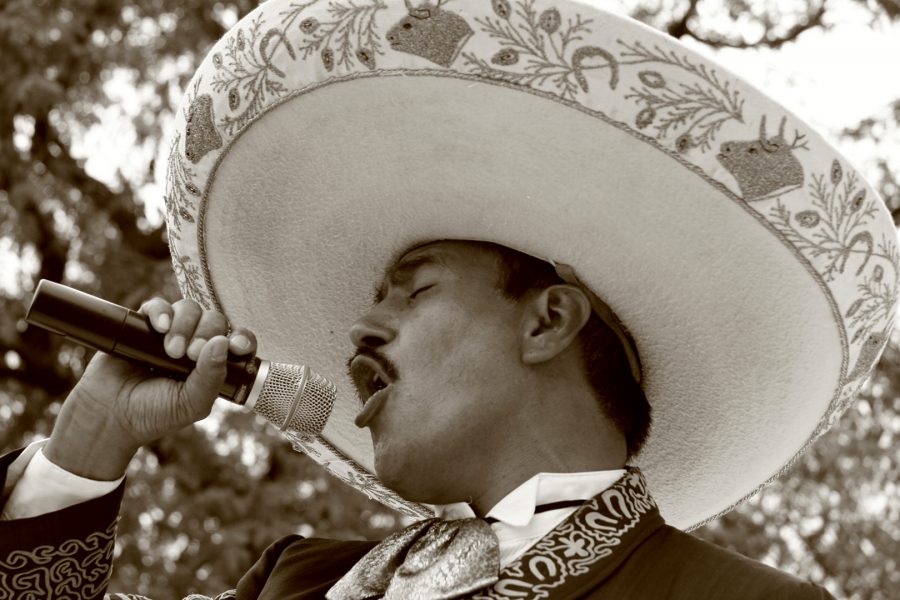

Nathaniel Salvatierra, 23, is a music performance major at Cal Poly Pomona. He is also a mariachi based out of Walnut. He has been doing mariachi for five years.

Salvatierra was not always so in tune with his Mexican heritage. His father was a part of a group of Central and South Americans who came to the United States who mostly disregarded their heritage and became americanized. His father was also very prejudiced towards Mexico.

His mother, who is also of Mexican descent, grew up very americanized as well because her distant cousin allegedly helped plan the assassination of Pancho Villa.

“So with that internalized racism and nationalism from my dad… in combination with my mom not knowing anything of my Mexican culture I actually didn’t understand mariachi music at all,” he said.

Salvatierra grew up listening more to rock and metal instead of latino music, only to find his love of mariachi through college.

Salvatierra went through his formative years playing bass for punk, metal and reggae bands. While at Cal Poly his professor Dr. Jessie Vallejo asked Salvatierra if he would be interested in playing guitarron.

“I was open to the possibility of playing mariachi music,” he said. “I thought it would be easy.”

Contrary to his statement Salvatierra soon found out it wasn’t going to be so easy. Quickly he realized that it was going to be difficult and that his preconception of mariachi music at the time was far from the truth.

Salvatierra said that mariachi is an oral tradition, and for a long part of its history it was not taught in classrooms with sheet music or tabs you can find. Rather, it was taught in a family setting or within the community by giving notes and picking it up by ear.

For a long time Salvatierra struggled with the songs, but he slowly learned the tricks of the trade.

Being an Instrumentalist while singing has been the biggest challenge for Salvatierra. Most of the songs are too advanced for him, and he does not have the experience yet. Most of the other mariachis are ahead of him when it comes to singing because he had no experience singing in ensembles with others. He never had to be in the forefront and was always in the background playing the instruments without having to sing.

“The best way to improve is to find little things here and there that make you feel uncomfortable for constructive reasons,” he said.

Mariachi used to be a world run by men, with so much as the thought of a female mariachi being taboo. The world of mariachi used to be very misogynistic. Women were not allowed to play, and if they did it was with an all female group or as a singer. You never saw intersex mariachi.

Mariachi hall of famer Rebecca Gonzales came down from San Jose in the 70′s and came to Los Angeles to play at the restaurant La Fonda de los Camperos. Grammy winning mariachi superstar Nati Cano himself asked Gonzales if she would play in his group Mariachi Los Camperos de Nati Cano full time. Accepting his offer, she would become the first woman to break into the previously all male world of mariachi.

“That was a major hit to the social norm of not having a woman in an all male group,” Salvatierra said. “Nati Cano received a lot of flack from patrons and other mariachis for having Gonzales in the group. Gonzales was the reason those social norms were shattered and she paved the way for females to become mariachis.”

Salvatierra met his mentor Jessie Martinez through Dr.Vallejo. Martinez, a guitar player, helped Salvatierra progress in his mariachi skills, teaching him techniques and songs he could learn to help progress and sharpen his skills.

”His improvement has been leaps and bounds.” Martinez said. They would play together and Martinez would get on him a lot, especially about looking professional and representing a heritage that has been passed down for generations. “Punctuality and appearance is number one, and practice practice practice.”

Martinez then introduced Salvatierra to Rebecca Gonzales, who needed a Guitarron player at the time. Even though he was green, he was hired and became the guitarron player for Mariachi Tesoro de Rebecca Gonzales.

“It is a link to an identity I never knew I had,” Salvatierra said. Growing up americanized, he never knew he had this connection. He had held contempt for his own identity. He did not have to dig deeper into who he was. He has since tapped into an understanding of people and emotions that he had never thought of before. “I had never had a sense of self before,” he said.

The artistry of mariachi for Salvatierra comes from the lyrics of the songs. The poems that the artists write are what hit him with feelings, and he loves the songs about romance. Those are the songs he can sing best and enjoys playing the most.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a struggle for Salvatierra and the rest of the mariachi world, but thanks to the friends he made through mariachi, he is getting through it. ”Mariachi music is about community,” he said. “It is the music of the people.”

The thing Salvatierra can not wait to see again is the audience’s reaction to their playing. One of his proudest moments was bringing an entire group of people to tears. It was the first time he was ever requested to sing. He was proud that he was able to get that reaction and was taken aback that he was able to move the audience, showing the true power of mariachi.