Fear, darkness, and a restless existence are some of the many experiences domestic violence survivors endure each day.

Oftentimes alone with their abuser — unseen and unheard.

For a few young women, a calling to serve as a source of light and strength for survivors of domestic violence, the journey started in 1977 in Claremont, CA, when a group of graduate students shared ideas for their final class project. During the debate, one student broached the topic of domestic violence. Although daunting to present real solutions for change, the group harped back to the words of renowned anthropologist Margaret Mead, “never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

Determined and fortified, the graduate students established a hotline led by volunteers in their local community. To their surprise, calls for help would seemingly come in endlessly. It became clear to them; that a greater need for those hurting would soon be approaching. They officially established the non-profit entity today known as the House of Ruth, providing over-the-phone and in-person counseling for victims of domestic violence.

Counseling sessions would only be half the battle, as many victims were also seeking refuge. In 1981, with the help of the Ontario Community Foundation, House of Ruth opened its first 18-bed shelter, which filled within 48 hours of opening. Fast forward to today in a world where current events are new nearly every morning, ranging from, international conflicts, a volatile economy, social crisis and endless causes vying for public funding; the unseen and unheard still seek shelter, searching for those who can listen, who can help.

Yet despite the times, a group of individuals continue the legacy of their predecessors, changing what they can, doubting nothing.

One individual is City of Pomona Councilmember Nora Garcia, who has devoted herself to the service of others since her early days in college. Garcia has put in over 300 hours as a volunteer in one year during her time as a student at Saint Mary’s College in Northern California. It was there, however, that her notions of domestic violence became real.

“Domestic violence is not something you speak about as a child [or] teenager,” Garcia said. “[However], some time ago the conversation started … I became more aware of my feminism … joining women’s groups … and it was definitely known.”

One example Garcia remembers vividly was the time she joked with an upper-class student about red welts on her arm. It was due to carrying a heavy bag of books but Garcia told her college that her boyfriend caused it. “I was joking; she knew my boyfriend at the time and her face just completely changed [asking] What did he do? Are you okay? That’s when I realized the gravity of domestic violence,” Garcia said.

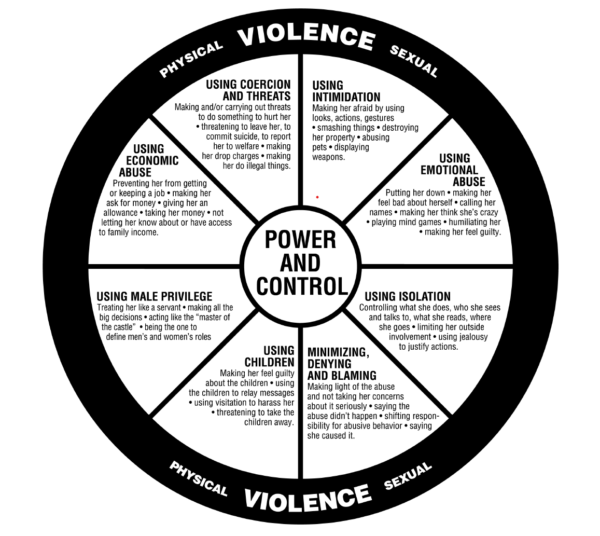

Gracia points out that domestic violence is a pattern of abusive or coercive behaviors that are all about power and control.

However, there can be various factors involved that cause domestic violence. Ashely Spencer, the volunteer manager at the House of Ruth is passionate in identifying those factors and sharing that data with the public.

She began her journey with the House of Ruth as a volunteer in 2011, after completing her 40-hour mandatory training. A year later, she became part of the staff, working at a crisis center as a case manager for two years.

Drawn to the education side of her job, she would later pivot and oversee the prevention team at House of Ruth where staff and volunteers go out into the community and educate the public on domestic violence.

Domestic violence functions on what’s known as the “cycle of violence,” consisting of three stages: tension building, explosion and the honeymoon stage. “Tension” is increasing irritability to internal or external forces that the person who causes harm feels. “Explosion” is the physical or verbal reaction inflicted on the victim that was caused by the built tension. The “honeymoon” stage is where the person who caused harm tries to redeem the relationship with either promises or pass guilt upon the victim for causing the tension and explosion.

The National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence explains this cycle through a diagram they call the “Power and Control Wheel.” In it, one would find various ways an abuser could keep their victim isolated and helpless. Ranging from verbal threats, intimidation, financial insecurity, using children or male privilege. Time, however, has changed the roles of genders and who normally plays what part. Though their report rate is lower than women due to the stigma of society, men too are survivors of domestic violence. Men get overlooked by the public and therefore never receive the help that’s readily available.

“There are so many layers to domestic violence … that it always doesn’t have to be physical … so, we serve all individuals regardless of their identity,” said Spencer. “This is evident through the House of Ruth’s versatility and inclusion within the community, ensuring anyone who needs help can get it. LGBTQ partners who have experienced domestic violence can find a place of understanding and receive professional and compassionate help that may not be offered anywhere else …”

“We try to take away as many barriers as we can so that it’s easier for them to leave [the abuse],” Chief Developer Officer for House of Ruth Rhonda Beltran said. The ability to serve, shelter and accommodate are markers of the House of Ruth. Yet their ability to maintain that status was challenged when COVID-19 hit.

On March 4, 2020, Gov. Gavin Newsom issued the “Stay at Home Order,” which directed the general public to stay home and businesses close to reduce the cases of COVID-19 surging through California.

This would become a living nightmare for domestic violence survivors. The “Stay at Home Order” restricted the number of people within a gathering of any type. It also restricted the area of space those who were affected could occupy.

Thus, for those in despair, living in close quarters with nowhere to go, the pandemic became the means for “power and control” for the abuser. “The person that caused harm was home [all day] with the victim …” Beltram said. “When the order was lifted, our hotline calls increased by 85%, because … the person who caused harm was not home, [therefore] the survivors were able to get a phone call and get help.”

Although the coronavirus created many problems for everyone, it did give people the opportunity to shine in a new level of generosity. “I had people who never called me before, asking me how they can donate … we saw an increase in giving in COVID,” said Beltran.

Beltran explained that advocates used various means of communication to get the message of domestic violence across during the coronavirus lockdowns. Causes to get behind and support can be a good feeling for those generous donors, regardless of the money or time they give. Yet, today there is a cause for everything. Especially if it can generate political points with voters.

Taxpayers want change. Positive change. Immediate, humane, and efficient change. Homelessness and mental illness are two of the many causes taxpayers want politicians to engage and fix. Yet, the general population wants it to change, more so because they see it. Homelessness and mental illness are things the public sees and experiences.

Domestic violence, however, is not a shared experience with the public. Nobody on the outside sees it.

It’s behind closed doors, keeping people imprisoned by intimidation and fear. By threats. Spencer believes educating the public and making domestic violence more of a community issue instead of one individual’s struggle can turn the tide. Domestic Violence Month is also the same month as Breast Cancer Awareness Month.

Yet, one often overshadows the other.

To make domestic violence the community’s problem, society must address its realities more frequently.

“With domestic violence, we have to hold someone accountable for the abuse, and that’s uncomfortable for people,” Spencer said. “It’s easier to talk about cancer because there’s no one to blame.”

Blaming someone is not the end state for curbing domestic violence. Though controversial to some, Batterer Intervention Programs, a 52-week rehab using alternative and formal means of therapy, seeks to address past problems in abusers’ lives that may have contributed to their behavior.

Regardless of public opinion, House of Ruth seeks total family care concerning domestic violence and plans to implement programs to help those who cause harm to change.

“A lot of times … people in these types of relationships don’t want the relationship to end, they want the abuse to stop,” said Spencer.

Yet, there is no guarantee that the guilty party will complete the training seeing they are the ones paying for it. This shows how complicated it can be to offer a comprehensive approach toward change. Nonetheless, the House of Ruth continues to demonstrate their willingness to help and guide all of those who are involved and affected by domestic violence. Perhaps another step of faith will soon be needed and taken.

For more information on the House of Ruth visit their website or call their 24-hour hotline at 1-877-988-5559 for immediate services.