2, 1, 3, 4, 4, 2, 1, shoulder tap, 5, 2, 1, 3, 4. What pitch am I throwing – a fastball, curveball, changeup, slider, splitter, sinker, cutter or forkball?

Don’t know? Well, you have 400 milliseconds to decide.

It’s the bottom of the fifth inning of the 2019 MLB ALCS between the visiting New York Yankees and Houston Astros. With no outs, bases empty and the Bronx Bombers leading 1-0, Astros third baseman Alex Bregman digs into the batter’s box looking to tie the game up. As Bregman awaits the first pitch from then Yankees starting pitcher Masahiro Tanaka, former Yankees catcher Gary Sanchez lays down a series of numbers for Tanaka to decode before he fires a first-pitch slider.

What stood out to me during this particular at-bat was Sanchez used a full sequence of pitches despite no men on the bases for the Astros underscoring the paranoia and importance of protecting their signals. As we continued watching the game in my living room apartment, a flatmate of mine asked, “Hey Robbie, what do the numbers mean?”

Without getting too technical, I explain to her that the catcher is telling his pitcher what type of pitch to throw and that the reason for multiple signs is to deter the opposing team from deciphering their signals.

As many baseball fans are aware, the Houston Astros were later busted after the 2019 MLB season concluded for sign stealing using a centerfield camera to relay the opposing catchers’ signs to the dugout where personnel in the dugout would bang on a trashcan to relay the type of pitch in real-time. Since then, the MLB has switched to a digital PitchCom system to deter teams from sign stealing. Although a majority of MLB pitchers and catchers have switched over to PitchCom, there are still pitchers who prefer hand signal sequencing.

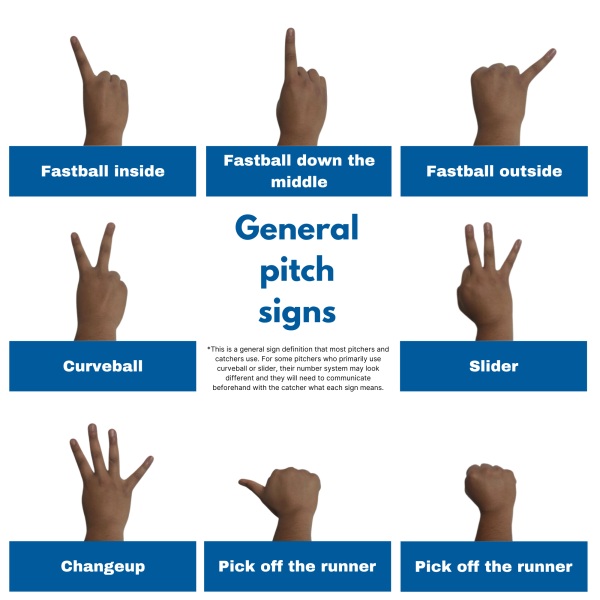

Is there a specific meaning behind each signal that is given?

Yes. The most common way for the catcher to relay a sign to the pitcher, or call a pitch, is using the fingers of his throwing hand. The signal is given from the squatting position and the hand should be positioned between the legs and be back up against or close to your cup. Generally speaking, this is what the numbers mean.

Although there are exceptions to the rule such as pitchers with more than four pitches in their repertoire or pitchers who are primarily curveball or slider throwers, their signals may vary. It is imperative for both the pitcher and catcher to be on the same page prior to the start so they can execute the game plan and minimize the amount of runs given up. At the minor and major league levels, the sequences are far more complicated and with the advent of PitchCom, sign sequences are a dying art like the mid-range game in basketball.

We’ve all heard the saying, “Communication is the key to any strong and lasting relationship.” This is no different on the baseball diamond. For pitchers and catchers, communication on the verbal and nonverbal levels is pivotal for their success. So much so that there is a term in baseball coined to describe a pitcher and catcher collectively – the battery.

According to the Baseball Hall of Fame, the origin of the term “battery” in baseball was first coined by Henry Chadwick, an American sportswriter and baseball statistician known as the “Father of Baseball,” in the 1860s in reference to the firepower of a team’s pitching staff inspired by the artillery batteries then in use in the American Civil War. Decades later, the term evolved to indicate the combined effectiveness of pitcher and catcher.

Each of these pitchers has said they have a preferred catcher because of one common denominator – the trust built from the catcher to call an effective pitch sequence to maximize their stuff, navigate a lineup with minimal runs allowed and of comfort knowing their catcher can block a bounced pitch to allow the pitcher to just throw.

But when did catchers and pitchers start using signs to communicate pitches?

While there isn’t a single specific source of information on how deaf players communicated with each other and with deaf umpires, they likely used sign language and gestures for plays, calls and other relevant game information since the inception of baseball in the 1840s. Mutual communication was key, not one-sided between umpires and players.

Deaf baseball started with sandlot games in 1865 at the Ohio Institution for the Deaf in Columbus. These players formed the first deaf semi-professional team, the Ohio Independents, and played nationwide. They followed the same rules as hearing players, using sign language and gestures for communication.

Hand signals and flags were probably used, unofficially, as early as 1865 in games involving deaf schools. According to the Baseball Hall of Fame, by the 1870s, Chadwick was describing and prescribing hand signals among players. Catchers would sign to pitchers both the type and location of pitches, although initially, it may have been more common for the pitcher to sign to the catcher.

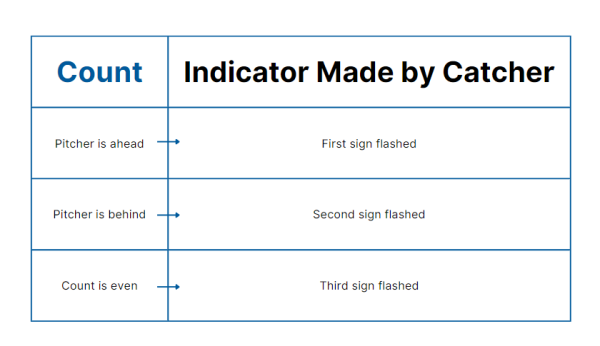

Here’s the secret to reading what sequence will be used. This is a simplified and potential way to indicate what pitch will be throw. If all teams used this, the sequences would all be easier to figure out.

What happens if you suspect your opponent is relaying signs to the hitter?

The adage “If you’re not cheating, you’re not trying,” is part of the fabric and essence of baseball. Sign stealing has been a part of the game since its inception. Decoding both tells and intentional signs in baseball has always been and remains legal.

Former San Diego State Aztec catcher Ryan Orr believes that the gamesmanship of trying to relay signs has been and will always be a part of the game.

“Sign stealing [without using technology] is not cheating. As a catcher, I know that if I’m not on top of my game and use a sequence that is easily interpretable, then I’m not doing my job. But if I catch someone or think someone is relaying signs to the batter, I will tell the batter, ‘Hey, you know your boy [out on second] could get someone hurt.’ If I can decipher the opposing catcher’s signs when on second base, there are subtle ways to tell my teammate in the box what’s coming. It goes both ways.”

However, this form of gamesmanship can get teammates hurt and incite brawls. In the 1800s, telescopes or binoculars were used to look at the catcher’s signs from centerfield and would relay the signs to the dugout in real time using an electrical wire connected to a buzzer or a scoreboard operator. The then New York Giants during the 1951 NLCS during home games would have a representative of the Giants use a telescope to decipher signs of the opposing team from the owner’s box above centerfield. A buzzer system wired to the bullpen and the dugout was used to relay the signs.

Sound familiar? Let me bang on a trashcan for you.

Typically, a catcher or coach will catch the opponents on second base relaying signs to the hitter. The way pitchers and catchers can defend against sign stealing is by calling a mound visit to alter the sequences. If a pitcher suspects someone is relaying signs, they can get back to a certain pitch by adding or subtracting indicators using non-verbal communication. It could be the pitcher rubbing their glove on their jersey twice, touching their ear, a head shake in a certain direction or if you’re Zach Grienke, telling your catcher mid-at-bat that they are stealing signs and changing the sequence.

Although today’s modern iteration of sign stealing has taken the gamesmanship too far, it only highlights the importance of communication between the pitcher and catcher to create a sequence they will understand and create defenses to prevent their signs from being stolen.