Questions Still Unanswered as County Vows to Uphold Services

County’s Health Officer asserts West Covina’s resolution will “change nothing” for now

After a controversial vote to pursue the creation of a local health department in the city of West Covina, Supervisor Hilda Solis provided residents with a town hall meeting on March 11 to explain the services the county currently provides and to answer resident questions on the issue.

The 4-1 vote, which was approved at a contentious special meeting on Feb. 23, was billed as an agenda item to cut ties with Los Angeles County’s Public Health Department relating to their, “orders and quarantine regulations prescribed by the state department of public health.”

Council member Brian Tabatabai, who objected to many aspects of the plan at the meeting, was the lone opposition vote.

In short, the resolution’s wording states that this break with the county would result in the city losing county services as of July 1. Since the resolution was passed before the March 1 deadline to file such a resolution, which was what triggered the special meeting, the resolution was in line with California Health and Safety Code section 101380 and would effectively separate the entities.

Los Angeles County Health Officer Muntu Davis, however, presented a different narrative alongside Regional Health Officer Noel Bazini-Barakat and Environmental Health Director Liza Frias for the town hall.

Nothing Will Change Unless Certified

Despite zero references to the health code section within the resolution, Davis argued that nothing significant would change to the city and county’s relationship because of Title 17 of the California Code Of Regulations, subsection 1276, which outlines all of the basic services a public health department must provide.

Thus, according to Davis, until the city’s health department became recognized by the state, the county would continue to provide services for West Covina. This effectively implying that the legal codes and resolutions would be null until the state recognized this new department.

It was unclear whether this was a rejection of the notion that West Covina would be creating a full-service local health department or a rejection of all options that were mentioned in the staff report. Other provided options for West Covina at their special meeting included a basic limited local health department and negotiations of authority and duties with the county.

While no option was fully explained at the meeting, and the third option would require a new contract with the county on legal grounds because of the resolution the city passed, Davis’ responses to resident concerns repeated one message.

“We still haven’t changed and we’re not changing until the city has a recognized local health jurisdiction and is capable of taking on those responsibilities,” Davis said in response to a question asking if the city could go back to the county after determining they could not handle this move. “Until that time, we continue to do what we do as the county health department.”

By recognition, Davis is referring to the state’s system to check whether a health department meets those title 17, section 1276 guidelines. This recognition emphasis follows another point Davis made during the presentation portion of the town hall, where he explained that even though West Covina wants to break off from Los Angeles County, they will still have to follow the same rules from the state that the county follows and will need their health officer to perform the same 171 unique duties.

The funding will also be a problem for this proposed local health department, as the county receives 69 percent of its funding from federal (50 percent) and state (19 percent) funds. Around 14 percent is charged to each city, 10 percent from local grants and 7 percent from fees.

Rounded, these numbers breakdown into: $760 million from federal, $287 million from state, $210 milion from the county, $154 million from local and other revenue and $104 million from fees to fund the department.

The numbers only get more confusing.

Fuzzy Numbers

While the council approved the move without a full comprehensive financial analysis of the fiscal impacts, the data provided by the county also raised several red flags.

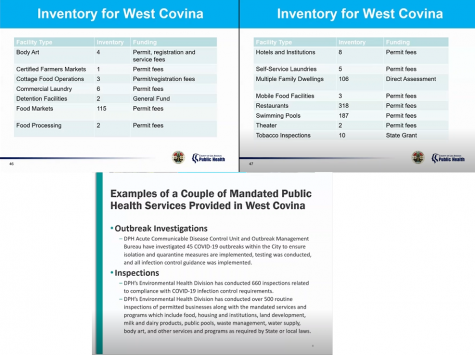

The first notable dataset was the classification of 660 inspections within the data that the county had provided.

If you use the county’s provided data within the presentation, the 660 inspections would be mostly from three types of sites.

Around 620 of the 660 inspections would be from pools (187), food markets (115) and restaurants (318) alone. This would leave 40 other inspections to other sites with all of those sites being checked once.

This makes the county’s provided total of 772 sites another concern, because the city staff listing on the Feb. 23 agenda report lists a total of 434 sites that would be covered under the proposed local health department.

The two reports also vary by what each entity considers within its jurisdiction. The county slides include pools but not medical facilities, and the city staff report includes retirement homes but not laundromats (which the county split into two separate categories).

It is also unclear whether both lists are incomplete snapshots of the city’s bigger picture or if both lists are intended to be all encompassing of what each entity oversees.

Regardless, both entities vary on the metrics by significant figures.

For reference, the county’s food sites alone totaled 442, where the city listed food sites totaled 214.

On a similar note, the restaurant category has a large discrepancy between the two entities. The county lists the city as having 318 restaurants where the city lists a total of 183 restaurants.

The closest metric between both entities was the county’s “body art” category of four businesses and the city’s “permanent makeup/tattoo” category of five businesses. Only that category and the restaurant category were directly shared between both entities’ lists.

City staff at one point asked about these numbers and how there could be 660 inspections on under 200 restaurants, but the county representatives did not provide a clear response to whether these inspections were conducted multiple times at locations or what the metrics broke down to.

Similar questions on an estimated $10 million that the city and its residents pay in taxes was left unaddressed.

“I think that’s a CEO question, a county CEO question, the net county cost dollars that are allocated to the department are done by the CEO, the county executive office, as part of our overall net county costs,” Davis said in response to the question. “I don’t know what proportion if any of it comes from the property tax, so I couldn’t answer that question.”

Aside from the proportionality questions of fairness, the county officials responses have been understood by some to mean that even if the city does make a health department, that assessed money will still go to the county, regardless of the passed resolutions, until the state recognizes the health department.

If that understanding is correct, with assessed fees and lost funding, the city will struggle to fund the department, as current assessed funds for the department would still be directed to the county.

Looking into the county’s posted data outside the town hall meeting also raised flags.

The county dataset lists 432 inspections in the city for the start of 2020 until March 4 of this year for an overall total of 763 inspections. Within this dataset, that 660 inspection total cannot be confirmed or understood and its accompanying 500 additional routine inspections are also vague.

Further, the 19 citations issued by the county in West Covina from Oct. 16, 2020 until March 5, 2021 can also be found online. This total impacts 11 businesses, including Bun Street who has had two individuals speak before council regarding their citation and dealing with the county.

Of the 11 businesses, eight citations are against the Self Made Training Facility, two citations to Fitness 19, and one to all other listed businesses. For the businesses that were cited multiple times, the average time in between citing was around a week.

City staff has pointed to a potential error within the population data provided by the county in one section on the main vaccination dashboard.

Their rationale did not contain the distinction between the data sets, that the county’s figure of 86,215 refers to residents 18 and older (as labeled on the dashboard), where a full Census figure of over 100,000 includes individuals under 18.

There are still potential issues with this data but the methodology of comparison to discredit the data is incorrect. See the correction for further clarification.

This potential error leads to questions of if the provided vaccination percent rate is correct, and whether any of the other data provided on the website, or in the town hall, are accurate or vetted with such a significant error on their public dashboard.

If further queries to the county and city explain this data further, this section will be updated to reflect any and all corrections and clarifications of these fuzzy numbers.

Reception

Residents had mixed responses on the Facebook discussion threads, some felt they had no say on the matter, some felt confident it would not go through, and others like Peggy Martinez, who is trying to get a petition to revoke the prior council vote, were further mobilized by the information.

“I watched and there is no way we as a city can afford this. You will need to have all the services and all the full time staff to go with it. Doctors and nurses are expensive. West Covina residents need to go to Tuesday’s meeting and show the power of the people,” Martinez wrote on Facebook.

Other residents, like Emylou Vergel de Dios of Change West Covina, echoed these sentiments.

“We don’t have the infrastructure, we don’t have the institutional knowledge,” she said about the issue. ”It will take a good amount of time until we have the funding for it to meet state requirements.”

Change West Covina, in its official capacities, will be joining Martinez to get the required signatures for the petition to reverse the council’s decision once the required legal documents are received and approved by the city clerk.

“Change West Covina is very committed to getting those about 7,000 signatures required so that we don’t have to do our own public health department,” Vergel de Dios added.

Many concerns were raised during the town hall presentation, and several council members were in virtual attendance asking questions.

None of the council members received a straight direct answer to any of their questions regarding the money or its allocation, which prompted some, like council member Tony Wu, to consider the meeting a waste of time.

While some residents feel council meetings are a waste of time, the council will nonetheless be having its own meeting on March 16 to discuss ordinances on setting up a local health department along with further information about the city’s plan going forward.

Despite the many issues and concerns with what was presented, Mayor Letty Lopez-Viado found some benefits in the presentation and what it can do for some residents as the city looks to move forward.

“It reassures our residents that they will not lose services until the completed transition,” Lopez-Viado said about the meeting. “We can all still work together.”

Correction: April 4, 2:50 p.m.:

It has been pointed out in an earlier version of this article that the following sentence needs to be updated for clarification:

Incorrect county data that was pointed out in the last article regarding West Covina’s population size is still up and remains unchanged (86,215 for 2019, versus US Census’ 105,101 or Suburban Stats’ 106,098 for 2019).

This has been amended to an “unverifiable” claim that the city is claiming that the county is incorrect. The changes to this part point out the difference in populations of individuals under 18 from roughly 19,800 from the county, 22,071 from the Census and 26,054 from Suburban Stats.

For reference, these estimates are derived from their respective websites, and the county’s figure is from pulling the highest population of 106,098 (the same population for Suburban Stats), where the Census has an estimated population of 105,101.

Subtracting these numbers you get a difference of population for 18 and older of 86,215 for the county in 2019, 83,030 for the Census and 80,044 for Suburban Stats. This difference in population is significant, but due to being unable to determine the methodologies for each population estimate, this information is kept to this correction and removed from the story to avoid confusion.

Due to the vast discrepancy and previous allegations by city staff and officials that the numbers are inaccurate, this section has been updated to more accurately describe the discrepancy:

The city said the county had incorrect data that was pointed out in the last article regarding West Covina’s population size. This data is still up and remains unchanged (86,215 for 2019). This is because the 86,215 figure only includes individuals 18 and older where a full Census population (referenced in the city staff presentation) includes the entire population including children 17 and under. Further, a more comprehensive analysis and nuanced explanation of the actual population discrepancy is included in the issued correction.