Looking Through The Lens of a Prolific Rock Photographer

Henry Diltz ruminates on photography and philosophy

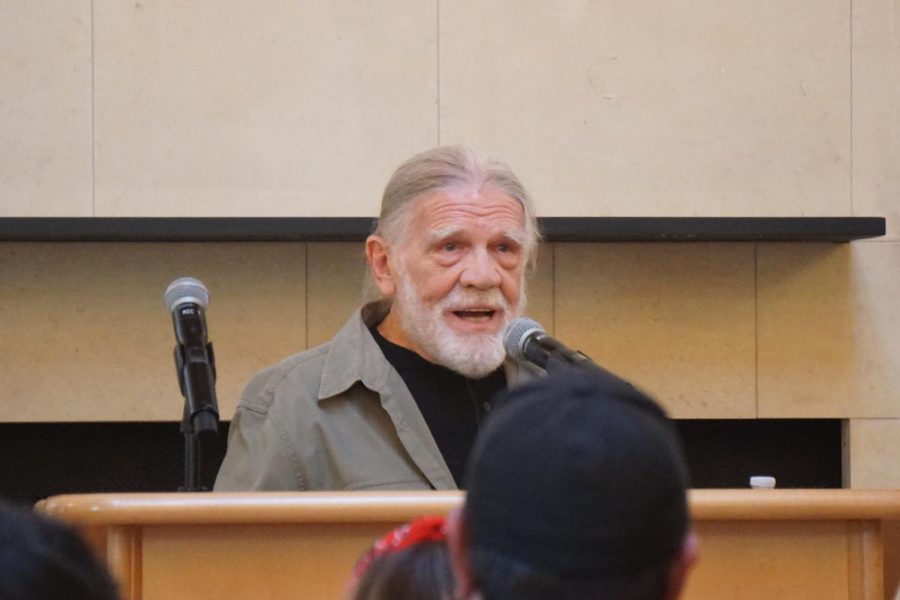

Henry Diltz presents a photographic slideshow at the Founder’s Hall on June 1

Boasting a remarkable portfolio that includes immortalizing the Doors’ “Morrison Hotel” album cover and Jimi Hendrix’s rendition of the “The Star-Spangled Banner,” Henry Diltz has cemented himself as a staple in the fabric of rock ‘n’ roll history as a musician-turned-photographer.

The psyche that empowered him to take such iconic photos extends far beyond the bounds of album covers and musicians. Gleefully capturing the spontaneity of rock stars, oddities of day-to-day life and unbidden words, Diltz embodies a natural curiosity and creative enthusiasm that not only shines in his work but enables its heights.

“My Chinese animal is a tiger. Tigers like to hide in the bushes and watch other animals. So I like to very quietly sit there and I don’t want to make a big deal about taking pictures because I want to see the real thing happening,” Diltz said in an interview with SAC.Media.

“I like to observe. I’m an observer type – observing and framing. That’s my two things.”

On June 1, Diltz – through organizational efforts by Claudia Lennear – presented a slideshow and lecture at Mt. SAC showcasing a variety of photos he has taken throughout his career and the histories that complete them.

An intergenerational crowd gathered within the Founder’s Hall to attend the event. Kindling full attention from attendees, Diltz commanded the room with wit and intrigue for roughly two hours. Although the slideshow of paramount musicians carried initial curiosity, Diltz’s humor, compelling storytelling and energetic conduct proved to be the main event.

Initially, a musician that was part of the band the Modern Folk Quartet, Diltz happened upon his photographic career on a whim. While touring with the group, Diltz and his fellow musicians bought cameras at a thrift store in Michigan. The impromptu nature of the pictures they were taking kindled his interest in photography.

“We picked up these little secondhand cameras and started photographing each other. We weren’t posing for each other. We were just snapping candid shots of each other when we least expected it,” Diltz explained.

“I was surprised to get it all developed the first time and see it was slide film; transparencies. And that’s when I said ‘let’s have a slideshow,’ and it kind of blew my mind when I saw these things projected really big, glowing in the dark. I thought ‘this was absolute magic.’”

Through the connectedness of the industry and geographical advantage, the pictures that Diltz snapped for fun began to produce commercial interest. Before long, he was being paid for his pictures and touring with bands to photograph them.

“It’s who you know. If I had been standing there having a camera in the middle ‘60s in Laurel Canyon – if I didn’t know anybody, I mean, I’d be photographing my foot,” he said. “It’s networking… that’s what makes the gears run.”

Some of the most iconic albums in rock ‘n’ roll history owed their accompanying photography to Diltz. The aforementioned the Doors’ “Morrison Hotel,” the Eagles’ “Desperado,” James Taylor’s “Sweet Baby James,” Crosby, Stills & Nash’s debut album and much more.

When it comes to distinguishing a favorite photograph – which would have to be procured through a collection of hundreds of thousands of images – Diltz came up short but posed an appreciative attitude for all his subject material.

“I was there for every photo I ever took,” he quipped in response to the question of choosing a favorite picture. “It’s all fun. Most of the people I photograph, I was a big fan of, I mean, I was a friend and a fan. They are all heroes to me… all those Laurel Canyon people I photographed, I really loved their music.”

In a similar vein, Diltz construed positivity and emotion as key components in the art of capturing a great photograph.

“To me, a great photo would be seeing a group totally candid, laughing, having a good time,” he said. “Life is a very positive experience, so when I photograph, I tend to take the picture when people are smiling or laughing.”

In a foreword in Diltz’s book “The Innocent Age,” art critic Saburo Kawamoto likened the atmosphere of his photography to that of a group of friends hosting a barbeque.

“Well, okay, that’s true,” he said in reference to the assertion. “I wait to see them smiling. I wait to see them looking good.”

Musicians are not the only focus of attention in Diltz’s vast repertoire. The scope of his photography extends from traditionally-alluring subject matters like animals and flowers to the quirky details of everyday life that may go unnoticed to less-inquisitive eyes.

“T-shirts, graffiti, tattoos, hearts… stars,” Diltz listed as items he takes photos of when he comes across them in his travels. “Fire hydrants is one because every little town in the country has a different color fire hydrant. So once you take two or three of those, you’ve got a series going.”

“Manhole covers, sometimes they are very interesting,” he continued. “So many things… the number series. Sometimes like 76 will be a 76 station and 57 will be a Heinz ketchup bottle. So I look for really odd places where a number will be. So then I go from 1 to 100 in a slideshow like that.”

Diltz credited such slideshows as the source of his photographic passions.

“When we were on the road taking photos, got them developed, they were slides – we had a slideshow. Then I thought ‘Man, I’m going to spend the week photographing all my friends in Laurel Canyon and then on the weekend we’ll have a big party and look at the slides,’ and that’s what we did” he said.

“In the early days, I wasn’t really shooting rock groups or well-known people… so I would look for interesting and colorful and maybe surprising pictures to show my, as I always say, my stoned hippie friends.”

Diltz’s creative endeavors do not cease at photography. A self-described frustrated painter, his spell with painting began in the ‘70s when he illustrated a photorealistic depiction of warm-toned tractors. Diltz also desires to reimagine some of his previous photographs by painting them. Although he does not actively paint, Diltz regularly writes.

“I have journals that I keep and I write,” he said. “I collect them – interesting sayings that I hear people say.”

Diltz developed this habit while touring with the Modern Folk Quartet. Member Cyrus Faryar roused laughter from the rest of the group with his distinctive form of speaking, to which Diltz attempted to enshrine Faryar’s off-the-cuff remarks with pen and paper – only for every person in earshot to forget what was said.

“I cultivated the habit of immediately whipping a piece of yellow-lined paper out of my back pocket and a Pantel out of my front pocket and I would just write it down,” he recalled. “I’ve got thousands of those pages.”

Diltz’s journals are lined with a variety of notable remarks, whether strung together through the rapid-fire word exchange of daily conversation or the scripted and refined dialogue disseminated through television. He brought attention to two quotes that he found indelible.

The first, from writer and philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti, was spoken in regards to Krishnamurti’s commendable propensity to weather the calamities of life: “I don’t mind what happens.”

The second is from “Saturday Night Live” character Father Guido Sarducci: “Don’t take life personally.”

Although Diltz could not recite spur-of-the-moment quotes off the top of his head, he hopes to one day compile his favorites into a book.

There are certainly parallels to be drawn between Diltz’s preferred mode of silent-observer photography and his record-keeping journaling. Technical processes aside – capturing light versus scribbling ink – both are means of tethering the non-replicable moments of the past to the present day for the purpose of appreciation in the abiding future.

As Diltz puts it: “It’s collecting a view of life.”

The philosophical aspects of his work are something that he has pondered. As an existentialist, Diltz emphasizes the importance of living in the moment, an ideal a smidge contrary to memorializing the past.

He wrestled with the seeming contradiction until it was made apparent to him that his work as a photographer is not antithetical to living in the moment but complementary to it.

“But one day some years ago, I thought… I’m not sure how I feel about being well-known for having all these old past moments, and then somebody said to me ‘Well, what you do is bring the past into the present’ and I said ‘Oh, okay – I can live with that,’” Diltz explained. “I am so happy I was able to preserve all these moments.”

Philosophical thought and spirituality intertwined with Diltz’s career since the early days. In the mid-‘60s, he read “Autobiography of a Yogi” by Paramahansa Yogananda, building the foundation for such introspection.

The lessons Diltz absorbed through the book led him down the road of Indian philosophy and similar teachings like those of Swami Satchidananda Saraswati. Through this, he has come to see life as a continuous learning experience.

“Everybody you meet potentially can tell you something, you can learn something from them,” he said. “Everybody is your teacher.”

The mingling of existentialism and Eastern philosophy bleed into Diltz’s ethos. Through this lens – living in the moment and learning from it – is his work best understood. People having the time of their lives, distinctive landmarks, numbers and interesting sentences – all, and more, provide innate value worthy of remembering.

“Keep your eyes open, keep your mind open, keep your heart open and see what life brings and relax a little bit,” Diltz said. “That’s got to be the most interesting subject. The reason we’re here, who are we and what are we supposed to do and why aren’t we doing it? That’s the thing right there.”