‘Don’t Fence Me In’ tells the story of injustice and resilience

Incarcerated Japanese Americans from World War II have their stories on display

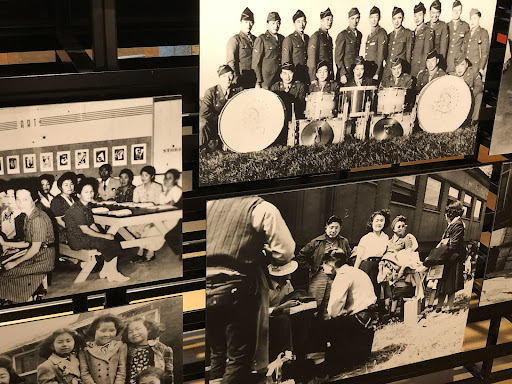

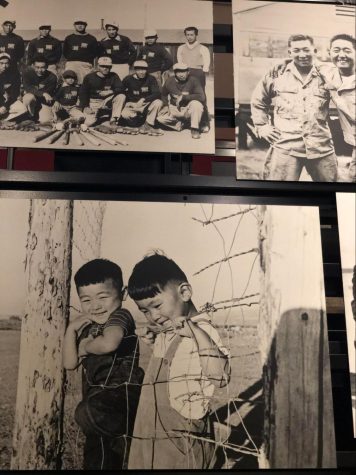

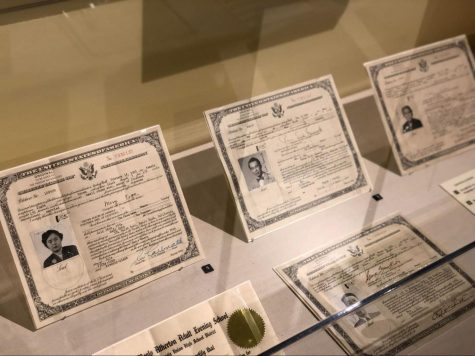

Photographs on display at the JANM show Japanese Americans who were detained.

Through photographs, personal stories and artifacts, “Don’t Fence Me In: Coming of Age in America’s Concentration Camps” reveals the strength and resourcefulness of young Japanese Americans who were detained in the 10 War Relocation Authority camps and the Crystal City Department of Justice internment camp.

The installment, which opened on March 4 at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, explores the injustice of over 120,000 Japanese Americans being imprisoned in detention camps during World War II.

Nicky Woo, a tour guide at the JANM, explained the decision-making behind Japanese immigration to the U.S. during this time in history.

“The Japanese were pushed out of Japan by drought and economic depression and pulled to America with tales of opportunity and promises of fortune and adventure,” Woo said. “Japanese immigration was part of a worldwide migration to the U.S. early in the 20th century, with the Japanese settling in Hawaii and the western U.S., and Japanese American communities forming plantation camps in those areas.”

The Chinese were actually the first large group of Asian immigrant laborers to enter the U.S. beginning in the 1840s. However, anti-Chinese sentiments rose from this immigration and culminated with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This law prohibited most Chinese laborers from immigrating into the U.S., so plantation owners began recruiting Japanese workers.

“Unlike European immigrants, Asians couldn’t become naturalized citizens and their status as aliens, who were ineligible for citizenship, confirmed they were unwelcomed to the U.S.,” Woo said.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, the U.S. government targeted Japanese Americans, with the FBI picking up and questioning Japanese men who served as leaders in their communities.

“The military dismissed Japanese American soldiers and segregated them into non-battle related tasks,” Woo said. “The Union Pacific fired Japanese American railroad workers on suspicion of sabotage. Many of the Japanese on the West Coast lost their jobs and the government classified them as enemy aliens.”

In February 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt issued an executive order authorizing the removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. The War Relocation Authority called the camps relocation centers, but government officials called them concentration camps.

“The government deliberately destroyed Japanese American communities on the West Coast and more than 120,000 people were incarcerated, two-thirds of them being American citizens,” Woo said. “The U.S. Constitution failed to protect their rights, a failure that affected all Americans.”

While the government prepared to sweep mainland Japanese Americans into camps, the scene in Hawaii was different.

“Japanese Americans made up 40% of the population and mass incarceration would have crippled Hawaii’s economy,” Woo said. “Instead the government declared Martial Law and perpetuated thoughts of fear and arrests.”

“It was impossible for Japanese American camp inmates to forget that they were prisoners, surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards,” Woo said. “They lived in communities based on rules established by the government that had set out to reshape Japanese American communities. Lack of privacy, long lines, cramped accommodations, group meals and bathing facilities caused chaos in the communities.”

In 1952, Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act, setting strict immigration quotas, but gave Japanese nationals and other immigrants the right to become naturalized citizens. Thousands of Japanese took advantage of the new law to claim their citizenship at last.

The Japanese American National Museum is located at 100 North Central Ave in Los Angeles. For ticket information and operating hours, visit the JANM website or call them at (213) 625-0414.

“Don’t Fence Me In” and the light it sheds on historic injustice towards Japanese Americans can be experienced until Oct. 1.